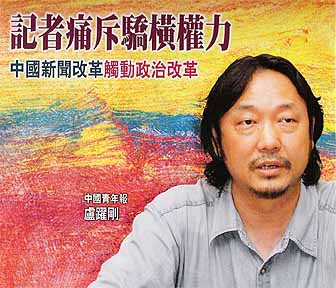

The Lu Yuegang Dossier

This post collects some information on Lu Yuegang, who is the author of a famous letter (see Link).

From the front cover of Yazhou Zhoukan (August

1, 2004 issue)

(Financial Times) Chinese media control attacked in letter. By Mure Dickie. July 24, 2004.

A Chinese journalist's eloquent protest against his newspaper's political masters has thrown a spotlight on the Communist government's media controls.

An open letter by Lu Yuegang, veteran reporter at the China Youth Daily, to a senior cadre at its parent Communist party Youth League has drawn widespread attention recently after being posted on the internet. The 13,000-character letter to League official Zhao Yong is the most public expression in years of the deep dissatisfaction of many Chinese journalists at the restrictions on their work imposed by party propaganda commissars.

It comes at a time of dramatic change in China's media as the government pushes reforms intended to commercialise newspapers and broadcasters by attracting foreign and private investment while retaining state control over content.

Mr Lu wrote that Youth Daily staff had long taken a pragmatic view of the role of a Communist party paper, "holding their noses" when filling news pages with the activities of Youth League leaders and "transmitting lies when forced to do so by senior levels". But a desire to be professional and objective journalists meant such accommodation had limits.

"The China Youth Daily can be a rubbish bin for the League central committee, but the paper itself must absolutely not be turned into rubbish," he wrote. "There will certainly be people to produce a garbage paper, but it won't be us."

Mr Lu's letter was prompted by Mr Zhao's speech last month to managers at the Youth Daily - one of the country's boldest newspapers - in which Mr Zhao condemned "idealistic" journalist practice and made clear dissent would not be tolerated.

Mr Lu accused Mr Zhao and his League comrades of undermining the newspaper's journalistic culture and seizing the opportunity provided by a scandal surrounding an erroneous article on prostitution last year to tighten their control. They had ignored an appeal by 70 editors and reporters for an editor sacked over the story to be reinstated. "Of course, in your excellencies' eyes, public opinion and dog excrement are both matters of no significance and you surely will not care about an unsightly mark on the historical record," he wrote.

But Mr Lu, who won international attention in 2000 when he and the China Youth Daily were sued by local officials in western Shaanxi province over a story drawing attention to a brutal acid attack on a local woman, also made more general criticisms.

The Maoist dictum that the party must control both "the barrel of the gun and the barrel of the pen" was hopelessly unsuited to modern China's needs, he wrote, blaming a harsh editorial in the party's People's Daily as a factor behind the bloody end to student protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Such bold criticism remains risky in China. But staff at the Youth Daily said Mr Lu did not appear to have been subjected to any punishment over his letter. Mr Lu and Mr Zhao declined comment.

(SCMP) Journalist slams party for 'taming' paper. By Naiele Chou Wiest. July 19, 2004.

An investigative journalist has launched a scathing attack on the heavy-handed interference that he says has turned the formerly spirited China Youth Daily into a docile propaganda sheet.In an internal memo, Lu Yuegang criticised the leadership of the Communist Party Youth League for intimidating staff and disregarding the paper's tradition of idealism and teamwork.

Lu's anger was directed at Zhao Yong , the No2 official in the Youth League's Central Committee, who visited staff on May 24 and told them the paper was not the place for "idealism".

The China Youth Daily journalist traced the changes at the paper to the handling of a controversial story run by its tabloid subsidiary, the Youth Reference. After a junior reporter wrote about female university students turning to prostitution in Wuhan , the reporter was fired and a senior editor dismissed for failing to exercise oversight.

A massive management reshuffle followed the scandal and while the changes poisoned the atmosphere, the newsroom was not tamed. More than 70 editors and reporters sent a joint letter to the Youth League's central committee asking for the senior editor to be reinstated, but their plea was rejected.

Lu admitted that editorial staff at the China Youth Daily had always walked a fine line between propaganda and professional journalism, but new leaders like Mr Zhao were seeking to rewrite the "rules of the game" and upset the balance. "The bottom line is that the league's Central Committee can place trash cans at the China Youth Daily, but it cannot turn the China Youth Daily into trash," he wrote.

Lu has been besieged by reporters since his memo started circulating on the internet, but he told the South China Morning Post that the Youth League had not tried to silence him. However, he does not want to speculate on what could happen later. "Things could change," he said vaguely.

Widely regarded as one of the finest investigative reporters of his generation, the 46-year-old Lu has never shied from controversy. He has been involved in many skirmishes with authorities, including a drawn-out defamation suit with officials of Shaanxi province over his reports on an assault case.

Born in Sichuan province , Lu had a haphazard education but his literary talent and stubborn willpower came to the attention of senior China Youth Daily editors, who gave him tough assignments and opportunities to conduct in-depth reporting. One of his former editors describes his reporting as "dynamite", which can blast open any cover-up.

Lu understands the importance of getting institutional support for reporters to withstand the pressure, which he said sets the China Youth Daily apart from other party mouthpieces on the mainland.

Liu Xiaobo, a veteran dissident fighting for press freedom, said Lu's memo was the sharpest criticism to date of official interference in the media. "As a respected journalist within the system, he is protesting against the insulting way in which a young bureaucrat is wielding his power," he said. "He is sending a powerful signal to the leaders that such outmoded ways of control must go."

A source at the China Youth Daily noted that Lu, who enjoys strong support from his co-workers, was not expected to be disciplined.

(Radio Free Asia) Top Chinese Journalist Calls For Political Reform. July 15, 2004.

A journalist at an official newspaper who is well-known for his articles about China's most disadvantaged, has called in an open letter for reform of the political system, saying it has become a matter of "extreme urgency," RFA's Mandarin service reports.

"This is not just related to the destiny of the Chinese Communist Party, but also to the prosperity and happiness of the Chinese people," Lu Yuegang, a journalist at the China Youth Daily newspaper, said in an open letter to the secretary of the standing committee of the Communist Youth League Zhao Yong.

The 1,300-word letter covered a wide variety of subjects, the Hong Kong-based Chinese language Ming Pao reported Wednesday, and included a reference to the bloody crackdown on student-led protesters by People's Liberation Army troops in June 1989.

Lu said he believed that the bloodshed was largely the result of a damaging editorial in the official Communist Party newspaper, the People's Daily on April 26, 1989, entitled "The necessity for a clear stand against turmoil."

Without the editorial, which was broadcast on national radio and television denouncing the student movement as a "well-planned plot" to bring down the Communist Party, the situation would not have deteriorated to an unmanageable state, Lu wrote.

The editorial—which was published while the more moderate Party secretary Zhao Ziyang was on a state visit to North Korea—prompted a strong reaction among students, who demonstrated in their thousands across China against the harshness of its language.

Lu said that the ruling party should take the demands of its people seriously, because as soon as the production processes are halted by problems in their relationship, social conflict will be the inevitable result.

One of the signatories to a November 2003 open letter from Chinese scholars and intellectuals protesting at the government's control of the Internet, Lu said that the task of the reform of the political system had become an extremely urgent one. "This is not just related to the destiny of the Chinese Communist Party, but also to the prosperity and happiness of the Chinese people."

Lu, who has referred to himself as a "hooligan journalist" in the face of injustice, has worked on the cutting edge China Youth Daily since the mid 1980s. He is well-known for his coverage of ordinary people who seek redress for abuse suffered at the hands of government officials.

(Time Asia) Taking On The System. By Terry McCarthy. October 9, 2000.

The moment the light went off in the small room in Fenghuo village, Wu Fang knew something terrible was going to happen to her. Three women from the village rushed in, knocked Wu Fang to the floor and began stripping her. Then her husband threw sulfuric acid on her face, chest and thighs. She let out a long cry. The women held her down, rubbing the acid onto her face and breasts, disfiguring her horribly for the rest of her life. Twelve years later she still seeks words for the pain: "It was like being thrown into the sky and hurled around."

Worse than the memory of the pain is the wall of silence that immediately fell around the village chiefs who were implicated in the attack. Powerful and arrogant, these officials from Fenghuo village in northwestern Shaanxi province have consistently blocked Wu's attempts to bring them to justice. When a Chinese newspaper wrote an article sympathetic to her case in 1996, the village sued for libel—and won in a local court this year. The case has been appealed to a higher court in the provincial capital of Xian, but the paper doesn't expect to win, despite growing interest in the case from lawyers and journalists in Beijing. "Everywhere in China there are outside factors that interfere with legal cases," says Wang Weiguo, professor of political science and law at China University in Beijing who has agreed to represent the paper in the libel case in Xian High Court.

For centuries China's rulers have struggled with corruption and lawlessness across their empire. Entire dynasties have collapsed after losing control over unruly provincial governors, warlords and self-enriching local officials. Today the Communist Party is facing the same nightmares—rampant corruption by officials at all levels, and growing discontent among ordinary people over the unaccountability of those who rule them. Every month sees protests by farmers or workers against corruption and illegal tax gouging by local officials. So explosive has the problem become that President Jiang Zemin has acknowledged it threatens the future of his government, and has issued edicts to crack down.

Last month the nationwide purge netted Cheng Kejie, the former vice-chairman of the National People's Congress, who was executed for taking $4.9 million in bribes for awarding government contracts. Since late last year hundreds of officials have been arrested or questioned in a $10 billion oil-, car- and cigarette-smuggling case in the port city of Xiamen. But despite Jiang's declaration of war on graft, cases involving powerful officials are still frequently held up or dismissed due to "lack of evidence." Even Jiang himself is reported to be protecting some of his friends. When the Xiamen case was on the verge of implicating the wife of Beijing Communist Party chief Jia Qinglin, a personal friend of the Jiang family, the President effectively blocked the investigation in January by appearing on television with Jia beside him. The corrosive effects of corruption have bitten deep into China's body politic, and will take more than a few decrees to be washed away.

Wu Fang's scars can never be washed away. Her face is ravaged. The acid ate into her right cheek and nostril, and her left eye has no eyelashes. Her right ear was burned off completely—subsequent second-rate surgery has completely covered up the orifice with a skin graft. She hears a constant buzzing and instinctively keeps trying to pick a hole in the skin with her finger. Hair has stopped growing on most of her skull, and she wears a wig to cover her baldness. Her hands are burned from where she tried to shield her face from the acid, and her breasts, stomach and thighs are covered in ugly scar tissue. She was once one of the prettiest girls in the village. After the acid attack her family removed all of the mirrors from her house so she would not see her own face. "I tried to kill myself several times after the attack—eating rat poison, climbing over the balcony in the hospital." Her attempts failed, and with her family's help she found the strength to go on. "I want justice," she says. "I believe heaven's law will prevail."

Born in 1958 in Beitun, not far from Fenghuo, Wu Fang left school at 15 to work in the fields. People in Beitun were envious of Fenghuo, which received large subsidies from the central government after it was designated a "model village" under Mao Zedong's policy in the 1950s of singling out villages, factories and individual workers as exemplary units of production. Fenghuo villagers received better houses, higher incomes and more food. The local Communist Party secretary, Wang Baojing, had been declared a "model worker" in 1957. He made frequent trips to Beijing, and claimed he had met Mao 13 times. Wu Fang's parents were delighted when a Fenghuo family said they wanted to arrange a marriage between Wu and their son, Wang Maoxing. (Fenghuo has six branches of Wangs, all of them related in some way to one another.)Wu Fang resisted, but her parents received gifts and money from Maoxing's family and finally in 1981, at age 24, she gave in and got married. The following year she had a daughter, but she quickly discovered that her husband—whom she had not met until they were married—was a layabout and a wife-beater. She did all the work in the fields while he stayed at home, and at night she did some sewing to earn a little extra money for the family. She was also head of the village women's federation, but the harder she tried to make her life a success, the more her husband hit her. "The whole village knew he was beating her," says Wang Xingxing, 58, a former assistant to party chief Wang Baojing. "They weren't suited. In the village we said it was 'like a cabbage spoiled by a pig.'"

Wu Fang asked for a divorce several times, but Maoxing refused to give his assent. "He said he would rather see me in a coffin than divorce me," says Wu Fang. Finally she couldn't take the beatings any longer, and in 1987 she ran away to Hancheng, a town 250 km away in Shaanxi. She changed her name to Dong Ping and tried to start a new life.

Wang Baojing was not in favor of a new life for anyone. As a model worker he was able to rule Fenghuo village like a feudal lord—a centuries-old tradition that survived, even flourished, under communism. If Wu Fang were allowed to abandon her arranged marriage and go off on her own, she could tarnish the reputation of the model village and even endanger the flow of subsidies and loans from the state. It threatened the entire old order. Somehow—Wu Fang does not know how—the village discovered she was in Hancheng. Wang Baojing called a meeting at which the village decided to send two policemen and her husband's elder brother to bring her back. In Hancheng they promised her a divorce if she returned. Wu Fang was skeptical, but she wanted to resolve the matter so she would be free to go back and visit her parents. "But when we got back to the village they drove straight past the courthouse where I should have gotten my divorce. Instead they put me in a room in the official village guest house." She realized she had been tricked.

That night her husband came to her room. "He said I was still his wife and had a duty to serve him. He tried to take my clothes off and have sex—I spent two nights fighting with him." Unable to have his way with her, Maoxing beat her badly. Her room had a lock on the outside, but not on the inside—she was completely at the mercy of the village.

On the third night—April 26, 1988—three village officials went into Wu Fang's room with her husband to make one final attempt at reconciliation. "That night the atmosphere was quite dangerous," says Wang Xingxing, the assistant to Wang Baojing. "There were 300 to 400 people standing in the courtyard outside." The villagers knew something was going to happen.

Wu Fang was adamant that she would not go back to her husband, and demanded the divorce she had been promised. The three officials tried to persuade her to reconsider. After one point, Wang Baojing's son, Wang Nongye, entered the room and told the other three officials to leave. After they had walked out, Nongye headed for the door, too. By now Wu Fang could sense the danger, and held onto his legs, begging him not to leave her with her husband. Nongye pulled himself free, and as he went out he switched off the light in the room. It was at that moment that Xingxing, standing outside with the crowd, saw three women rushing in. He remembers it was about 7 p.m. "Then I heard a loud scream—'Ma!' I saw the three women beating her, but I didn't know then that they had acid."

After the attack someone turned on the light in the room. Wu Fang was lying on her right side in a pool of acid—this is apparently why the right side of her face and her right ear were so badly burned. She was temporarily blinded. Xingxing heard one official telling others to dispose of the burned clothes, and then he realized what they had done to her. "Most people in the crowd felt sympathy for Wu Fang's fate, but nobody dared to go in because there were officials involved," says Xingxing. "Everyone thought it was too cruel, but nobody would denounce Wang Nongye, because since the '50s they had been trained by Wang Baojing [Nongye's father] not to speak badly of the village."

There was little mercy for Wu Fang, even after the attack. Around 9 p.m. she was loaded onto a truck and driven to the district hospital in the small town of Liquan. The doctor there said her injuries were too severe to treat. The village officials then left the semi-conscious—and still untreated—Wu Fang overnight in a bus station. "I think they hoped I would die," she says. The next morning they returned, and brought her to the No. 4 Military Hospital in Xian, about three hours' drive from Fenghuo. They left her there with $200 to pay for her treatment.

Wu Fang spent a total of seven months in the hospital. The $200 quickly ran out, and her mother went to Baojing to ask for more money to pay the doctors. The party chief turned her away, even after she went down on her knees to beg. Her family sold their belongings and the entire proceeds of that summer's harvest to pay for continued treatment for their daughter. When she was released in December 1988, she had had multiple skin grafts, but the military surgeons still had not been able to lift her appearance above the level of the grotesque.

The only thing keeping her alive was her determination to get justice. Wu Fang spent long hours badgering people outside the local courthouse and arguing her case with provincial officials. Her husband had been arrested in 1988, but nobody else had been investigated, and the local court kept returning the case to the prosecutor saying not enough evidence had been collected. Finally in 1991 a member of the provincial people's committee took an interest in her case and complained in public that nothing had been done about it. Shortly afterward, her husband was executed, and his brother, Maozhang, was jailed for providing the acid. The case seemed closed. "But they were just scapegoats—the real guilty person is Wang Nongye," she says. "When he turned off the light, that was the signal. They had planned it all in advance." All her attempts to have the investigation widened came up against an immovable obstacle—the power of Wang Baojing and Nongye. "Wang Baojing is so powerful that if anyone in the village wants a job in the nearby town, he can fix it," says Wu Fang. "He has a huge network of patronage—everyone is scared of him and his son."

Wang Xingxing, who worked for Baojing for 38 years until he retired in 1996, knows only too well how intimidating his former boss can be. "Wang Baojing is the kind of person who eats your food and then breaks your bowl," says Xingxing. He had a falling-out with Baojing in 1997 after the party chief suspected him of informing on one of his aides for beating up Wu Fang's mother. Baojing did not like anyone interfering with his business. As party chief of a model village, Baojing became rich. "In Fenghuo's history, whoever got money got it from Wang Baojing," claims Xingxing. When the government set up a cement factory and a paper-box factory in Fenghuo, "they became Wang Baojing's family's factories. The financial statements of the factories were never released. For example, I know the cement factory was making a good profit every year, but the village never saw any of it."

Wu Fang had almost given up hope of getting justice when she was contacted in 1996 by Lu Yuegang, a Beijing journalist for China Youth Daily. Lu had heard about Wu Fang's story from an acquaintance in Shaanxi. In August 1996 he wrote a story about the case, headlined "The Strange Affair of the Destroyed Face." The article questioned why nobody apart from Wu Fang's husband and his brother had been investigated in the case, particularly since witnesses say Wang Nongye was implicated in the attack. Lu's article also cast doubt on Baojing's record as a model worker dating back to the 1950s, during which time, Lu claims, the figures for Fenghuo's grain production were vastly exaggerated.

But soon after the article appeared, China Youth Daily found itself subject of a libel suit, brought by three defendants: Wang Baojing, Wang Nongye and the village of Fenghuo. They claimed that Nongye had been unfairly linked to the acid attack, and that Wang Baojing's reputation as a model worker had been seriously damaged. The newspaper retained several top lawyers from Beijing, including Wang Weiguo, the law professor, who also advises President Jiang on legal reform. Wang agreed to take on the case to make a larger point. A strong advocate of law reform, he believes China must have a legal system that powerful individuals cannot interfere with. "When I look at the evidence of this case, it is clear Wang Nongye should be a suspect—but he hasn't even been investigated," says Wang Weiguo.

But the lawyer quickly realized that the legal system works differently in Shaanxi province. His first lesson came when the plaintiffs demanded $600,000 in damages. When the judge asked why they wanted this amount, the village mayor replied in court that since the article had appeared, the apple trees in the village no longer bore fruit and the chickens had stopped laying eggs. "What kind of logic is that?" asked the lawyer, incredulous. When the judge failed to immediately dismiss such a line of reasoning, Wang Weiguo saw his chances of winning the case in that court slipping away. His fears were confirmed when Wu Fang was approached by an intermediary of Wang Baojing, offering to pay her $12,000 in exchange for her refusing to testify in court. Wu Fang turned down the offer, but by then she concluded that Baojing was trying to manipulate the legal process. Finally in June of this year the judge found against China Youth Daily, and ordered it to pay $11,000 in damages to the plaintiffs.

Wang Baojing declines to comment on Wu Fang's case or the associated libel suit he brought against China Youth Daily. Through a spokesman he said he has "no time to answer Time's questions." Wang Nongye did not respond to Time's attempts to speak with him.

It has been 12 years since the acid attack on Wu Fang. She has remarried—despite her outward appearance, a man in Hancheng proposed to her. In 1994 they had a daughter, who is now the center of Wu Fang's life. Wu Fang is a resilient, strong woman, but even now she cannot tell her story without breaking down and crying. Her eyesight has never fully recovered from the acid, and she still needs surgery on her corneas as well as corrective surgery to open an aperture for her right ear.

In Fenghuo, a cheerless village of 2,000 inhabitants constantly coated with grime from the cement factory, people don't like to talk about Wu Fang. "It is so complicated—it is a fight between officials" says Wang Wanchun, an apple farmer. Nobody has—or dares to say—a bad word about Wang Baojing. Now 70 and officially retired, his influence still extends from Fenghuo all the way to the provincial capital. Following in his father's footsteps, Nongye was declared a model worker in 1992 and is also an influential party member in the province.

Wu Fang has yet to find justice for what happened to her in the village guest house. But for Professor Wang Weiguo, who is still fighting the appeal, the case extends far beyond Fenghuo. "If a nation has no feeling of justice, that nation is dead," he says. There are many reformers in China who would like to see their country free of abuse of power by officials who answer to no one. But the acid has bitten deep into the system at all levels, and China needs more than cosmetic surgery to recover.

(Time Asia) Don't Go There. By Brian Bennett. October 9, 2000.

Workers at a textile factory in southern China complain to the local mayor that the managers are stealing money from the plant. The skeptical official, Li Gaocheng, investigates and uncovers a vast scam that involves even his own wife. He faces a dilemma—to squash the investigation, or push ahead and see his wife arrested. The plot of the film Choice Between Life and Death—which has been seen by more than 12 million people in China since being released in June as part of a state anti-corruption drive—is stark. Mayor Li, of course, never wavers, and his wife and all the corrupt managers are arrested and given long prison sentences.

But does art really imitate life? On the surface, China indeed seems serious about fighting corruption, and heads are starting to roll. Investigations have been launched this year into almost 23,000 cases of possible corruption. The former vice-chairman of the national legislature, Cheng Kejie, and the former vice-governor of Jiangxi province, Hu Changqing, have been executed in separate bribery cases. More than 100 officials are on trial over a $10 billion smuggling scandal in Xiamen, the biggest corruption case so far to reach China's courts. Last week the former deputy governor of Hubei province, Li Daqiang, was fired for accepting bribes, while the former deputy mayor of Shenzhen, Wang Ju, is currently under investigation for similar offenses. Also last week an inquiry was launched into a foreign-exchange and tax-evasion scam in Guangdong that may turn out to be even bigger than the Xiamen case: a stunning $12.2 billion apparently found its way into the pockets of provincial customs, tax and banking officials and Hong Kong businessmen.

President Jiang Zemin has put himself at the head of the anti-corruption charge. On Jan. 14, he told the Communist Party's corruption watchdog committee: "The more senior the cadre, the more famous the person, the more rigorously cases of violation of discipline and law must be investigated and handled." Yet only a week later Jiang was seen on state-run television strolling alongside Jia Qinglin, a Politburo member and Jiang's handpicked choice as Beijing party boss. Jia's wife Lin Youfang, who ran the largest state-owned import-export firm in Xiamen, had been implicated in that city's massive smuggling scandal. But with Jiang's very public show of support, all talk of Lin being arrested quickly stopped. Even Jiang, many Chinese concluded, was prepared to bend the rules to help out a friend.

High-level connections also reportedly saved the life of Chen Tongqing, the former party secretary of Zhanjiang, a southern coastal city. Chen was sentenced to death in May 1999 for taking bribes, but the sentence was suspended after senior party figures intervened. Such high-level favoritism risks further antagonizing citizens who are fed up with officials helping themselves to public funds. The National Audit Office estimates that $15 billion was embezzled in China last year, more than 1% of the nation's annual economic output. Across the country, social unrest caused by corruption and tax gouging by local officials is increasing, with protests frequently turning violent. Last month farmers in two separate provinces in the path of the Three Gorges Dam project marched on local government headquarters, attacking officials suspected to be lining their pockets with undistributed resettlement money. "The fight against corruption is vital to the very existence of the party and state," says Liu Liying, deputy secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection who is heading the Xiamen investigation.

Top connections don't help everyone. Cheng, the former vice-chairman of the National People's Congress who was executed in September for accepting $4.9 million in bribes, was a protégé of former Premier Li Peng. Li had helped Cheng into the position of governor of Guangxi after they met in 1986; when Li was made chairman of the legislature in 1998 he brought Cheng with him to be his deputy. Another Li protégé, Niu Maosheng, former head of the Ministry of Water Resources, is currently under investigation for allegedly misappropriating flood relief funds. And several officials managing Li's pet project, the Three Gorges Dam, are under investigation for mismanaging resettlement funds for the more than 1 million people the reservoir will displace.

The current Prime Minister, Zhu Rongji, is said to be fuming at interference in the Xiamen case. With his hard-nosed attitude toward reform, he knows that in the fight against corruption, China—and the party—face a choice between life and death.

(Time Asia) Muckrucker. October 9, 2000.

Lu Yuegang calls himself, only half-jokingly, a "hooligan journalist." When he sees things that are unjust, he goes mad. A hulk of a man with long sideburns and a warm laugh, Lu had been a reporter with China Youth Daily for 10 years when, in 1996, he heard the story of the acid attack against Wu Fang. He was outraged and flew to Shaanxi to hear her story firsthand. In August of that year his paper published his article, "The Strange Affair of the Destroyed Face." That's when the trouble started—in the form of a libel suit launched against him and the newspaper by the village of Fenghuo and its two most prominent inhabitants, local Communist Party secretary Wang Baojing and his son Wang Nongye.

Lu, a 42-year-old Sichuan native, was no stranger to controversy—he had already written a book criticizing the Three Gorges Dam, a high-profile project championed by some of China's highest-ranking leaders. Lu wasn't reprimanded for that, in part because other journalists had taken up the same crusade. With Wu Fang, however, he was on his own. And the more he dug into her case, the more obsessed he became with it. "She is an amazing woman," says Lu. "Anyone else would have committed suicide."

When the libel case was filed, Lu was gratified that his bosses at the paper said they would stand behind him. He braced for the fight, making several trips to Shaanxi for further research. In 1998 he wrote a 518-page book about the case, Big Country Small People. The book painstakingly reconstructed the acid attack and delved deeply into Wang Baojing's record as a "model worker." Lu found that claims of record harvests under Wang Baojing's supervision were largely spurious. He also cast doubt on whether Wang had actually met Mao 13 times as he claimed. "Maybe he saw Mao from a distance in Tiananmen Square," says Lu.

In June the court ruled against China Youth Daily in the libel suit, although the presiding judge declined to give any reasons for his verdict. Lu is determined to push on with the appeal, even though he realizes the chances of succeeding in Shaanxi's courts aren't great. He simply can't give up. "First, because of Wu Fang—she is just a villager, and she has had very unfair treatment. Second, because we all live under the same sun as Wu Fang—what happened to her could happen to us."

Last month Lu was in Xian for the opening of the appeal. On hand were several journalists from Beijing who had finally woken up to the story. Lu was upbeat until the day before the court hearing, when the judge suddenly announced that the session would be closed to the press because it was a "state secret." As Lu's lawyer went to protest the decision—in vain, it would turn out—Lu sat in a hotel coffee shop, cursing the system. "We never really thought we could win the case, but we hoped to tell people about it." Despairing, he posted a press release on the paper's website to announce that the court would be closed to the press—within minutes his mobile phone was ringing with calls from journalists all over China pledging their support. Lu brightened up: "I'm strong enough to fight these guys to the end. You have to be a hooligan to deal with hooligans." With corruption and abuse of power at record levels, China needs more hooligans like Lu Yuegang.