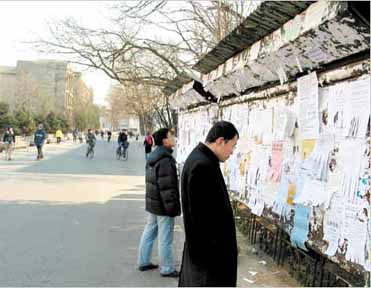

Democracy Wall, Beijing University, 2005

[photo: Cao Zhongzhi 曹中植

taken at 1:30pm on January 21, 2005]

[Boxun] [translation] The Beijing University "Big Character Wall Posters" for democratization have been replaced for job news.

Fifteen years ago when the Tienanmen Square incident took place, the Beijing University student notice boards were covered with big-character wall posters. Today, they are full of advertisements for English-language and Japanese-language talks, law exams, MBA test preparation classes and so on.

The photo above was taken at the Centennial Hall on the campus of Beijing University. This is the most famous student assembly area, known as the "Triangle Area" for getting information.

In the middle of the three streets, there is a board on which various notices and advertisements have been posted. During the demonstration for democratization in May 1989 at Tienanmen Square, the boards in the Triangle Area were covered with big-character posters in support of democratization.

On this day, the board only had various advertisements about "Japanese Language Study Class", "2005 MBA Joint Examination Study Class," "Intermediate English Language Lecture", "National Law Examination Study Class" and various other foreign language and national examination study classes.

It was a matter of international interest whether there would be a "Third Tienanmen Square Demonstration" as a result of the death of Zhao Ziyang. But it did not seemed to have stirred the Chinese students of the 21st century into demanding democratization. Beijing University was the principal player in the May 4 student reform movement and also the main force of the 1989 Tienanmen Square demonstration for democratization, but it is very quiet today. The students began their winter vacation on January 15, and most of them have returned home already for the biggest holiday period in China. The campus now seemed deserted. The Beijing University which stood up every time to protest historical injustices is silent today.

We encountered a third-year law student named Dai Xin at the Triangle Area. Dai only knows that Zhao Ziyang was a past leader of the Chinese nation. He said: "I don't know a lot about Zhao Ziyang. Therefore, I am not paying any special attention to this death." At the time of the Tienanmen Square demonstrations, Dai was six years old.

A certain Fuzhou student who is a doctoral students in the Life Sciences Department said: "The students are most concerned about their jobs and their futures. My biggest goal is to be able to work at a research institute for a large corporation after I get my degree."

In recent times, it is impossible to find any ardor for democracy and revolution among Chinese university students. We spoke to someone who took part in the May 1989 Tienanmen Square demonstrations who is now working for the China Development Bank. He entered the Guanghua Administration School of Beijing University in 1988. He said: "The Chinese university students of the 1980's are significantly different from the Chinese university students of the 1990's." The students who grew up after the economic reforms are more concerned about their personal problems than about nation, revolution and democracy. He said, following the "family planning policy" of the late 1970's, the individualism of the university students of the 1990's have really stood out. During the passing of the fifteen years, as a result of the blockade of information by the Chinese government as well as the individualistic tendencies of Chinese youth and university students, the matter of Zhao Ziyang and the Tienanmen Square demonstrations is now history and has no more traction in the politics of today.

As of today, the Chinese government still has not provided any details about Zhao Ziyang's burial ceremony. It is unlikely that the Tienanmen Square demonstrations for reform and democracy upon the deaths of Zhou Enlai and Hu Yaobang will appear again.

On January 18, the day after the death of Zhao Ziyang, we visited Beijing University and Qinghua University. There were no extra guards at the gates, and anyone can come and go freely. At the Triangle Area, which is center for political action in Beijing University, the notice boards were covered with various advertisements and notices, one on top of another and curling in the waves of cold wind. "Hot Pot restaurant welcomes your patronage", "Female student bedspace for rent", "Beijing High School Joint Educational Center is hiring family tutors", and so on.

Whenever there is a student political incident at Beijing University, these rows of notice boards which run as long as 100 meters were the weather indicator. The death of Zhao Ziyang had no impact here at all. We saw one male and one female student copying down tutoring information, and so we spoke to them. When we asked them about the death of Zhao Ziyang, they looked perplexed because they had no idea who he is. The female asked, "Which department did Zhao Ziyang teach in?" When told that Zhao Ziyang was a former general secretary of the Chinese Communits Party, they laughed in embarrassment.

The male student said that he is studying educational economics. The school exams have just been completed, and the students are leaving for their winter vacation. Most of the students from out of town have already gone back to their hometowns.

Jiao Guobiao believes that the sudden death of Zhao Ziyang will not cause a big impact on the social reality of China. "The principals in the incident fifteen years ago are today at least 35 or 40 years old. Most of them are facing the realities of life, and it is impossible to go across space and time of 15 years to continue. The new generation is unfamiliar with that era. The prime movers of the 6/4 incidence in 1989 were university students, who were the elite of society. Today, the most disaffected segment and most likely to take action are the petitioners, but they are socially marginalised and very few pepole care about them. For example, the wave of resistance at Hanyuan in Sichuan province last year involved several tens of thousands of people, and this happens in many places. But they took action in order to accomplish a very specific goal, and they made no political demands. There are two huge factors that can cause a political change in China. One comes from international conditions while the other would be when social opinion has reached an extreme point. When we speak of rotten fish, we say that the rot usually starts from the inside. At this point, I cannot see this happening."

For Yu Yang, a mop-haired biology major, the small notice posted this week on Beijing University's Web site about the death of a former Communist Party leader seemed like an irrelevant historical footnote.

Growing up, Mr. Yu, now 21, barely knew about Zhao Ziyang, except that he had "played a prominent role in 1989." And Mr. Yu acknowledged Thursday that he barely knew about 1989. He knew students had protested at Tiananmen Square; he had heard that Chinese soldiers fired into the crowds to end the demonstrations.

But Mr. Yu, an aspiring scientist, described that as hearsay. "Rumors say so," he said of a bloody crackdown witnessed by a worldwide television audience outside China, "but I need a lot of evidence to believe it."

If the Chinese government can help it, he may never see that evidence.

For years, the Communist Party has awaited Mr. Zhao's death with trepidation, fearing protests or riots. Purged for sympathizing with the students, then placed under house arrest in Beijing for almost 16 years, Mr. Zhao became a martyr to a generation of Chinese for whom Tiananmen remains an indelible scar.

But for many younger Chinese, who did not witness those events, he is a virtual nonentity, banished from history books and the state-controlled news media. At Beijing University, a focal point of political dissent in 1989, his death scarcely seemed to register with the generation of students who were children when the massacre happened. Some, like Mr. Yu, were simply ill informed, knowing about it only in vague, often inaccurate, terms. Others, frightened, knew they should change the subject.

Asked if any event in the news had seemed significant this week, one student standing in the doorway of his room replied, "You mean the Australian Open?"

When his visitor gave him a quizzical look, the student smiled almost imperceptibly. "Oh, you mean Zhao," he said.

The government's deep concern about the lingering anger over Tiananmen - and the potential that it could still be the match that lights new protests - explains the official response since Mr. Zhao died Monday. Dissidents were quickly placed under surveillance or, in some cases, under house arrest. The Chinese media were banned from covering his death, other than a small mention in state-controlled newspapers.

At elite universities in Beijing, security was increased, and faculty members were initially told to monitor their students to protect against demonstrations. Jiao Guobiao, an outspoken journalism teacher at Beijing University, said political speech was already tightly monitored long before Mr. Zhao's death, a fact that influenced the muted response by students.

"It's not that they don't care," Mr. Jiao said. "It's that they don't dare care. Any student who shows a concern for politics will be discriminated against. They will be sidelined, so they learn over time not to express opinions about political subjects like this."

Mr. Jiao himself is a telling example. Last year, he wrote a scathing indictment of the government's propaganda department. Since then, he has remained on the faculty but not been allowed to teach.

Meanwhile, a popular chat room run by Beijing University students was closed last year after the postings became increasingly political and often critical of the government.

Roger Jie, 21, a junior, laughed when asked if politics played a major role in campus life. "Very nonpolitical," he said. "Neutralized, in fact, pretty neutral. Students are used to not talking about it."

Mr. Jie, who grew up in Guangzhou, said Tiananmen was rarely discussed at his high school. Instead, he learned about it from a program on an uncensored Hong Kong television station. "The pictures were really brutal," he recalled.

Now, he said, the passage of time and economic progress in China have made Tiananmen seem less relevant to his life. "It was long ago, and there hasn't been much news about Zhao for 10 years or longer," he said. Asked if he now felt free in China, Mr. Jie paused for a moment.

"To a degree, it is free enough for me," he said, even as he insisted on using his English-language name.

Xu Youyu, a liberal political theorist at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said the government blackout of information about Tiananmen meant that many younger people were ignorant about what happened in 1989. "For this generation, it is not so important," he said. "They know very little or nothing about it."

In interviews with about a dozen students at a men's undergraduate dorm, several were not aware that Mr. Zhao had been general secretary of the Communist Party or that he had been under house arrest since being purged in 1989. Other students offered a softer gloss on the government's role in the crackdown.

"Many people left safely," explained a 21-year-old student from Anhui Province who asked not to be identified.

Did the soldiers fire on the students?

"It's really not clear," the student continued. "I heard the soldiers fired back when they were attacked."

His friend chimed in. "I don't care too much about politics," he said. What does he care about? "Soccer," he answered.

In another room, four students - none willing to be identified - played video games. One student, who is majoring in Chinese history, said college students had access to information on the Internet that was not available to most Chinese and were aware of the problems here.

But he thought that too much freedom of speech, too fast, was not a good thing. "We need to phase in freedom of speech step by step," he said. "Not overnight."

His friend added. "Overnight is like a revolution. Step by step is evolution. We oppose revolution."

On a different floor, a student who gave only his surname, Lei, watched music videos on his computer with a female friend. Mr. Lei, 22, said Mr. Zhao's death had had little impact on campus. He said he knew that historical events described on state television were often twisted or false. "We listen, and it's all good things," he said.

He switched off the music video on his computer and punched up something else from his hard drive: a bootleg documentary on the Tiananmen protests. He said the Internet was the primary source of information on the protests for students. But if he was interested in the truth about Tiananmen, Mr. Lei said he questioned the broad idea of Western democracy for China.

"This country has too many people," he said, echoing a line often repeated by government officials. "It's hard to manage, and it may not be a great idea to practice Western democracy. It may cause chaos."

Mr. Lei's friend, visiting from another university, stood quietly nearby. Asked about Mr. Zhao and 1989, she blushed. "I don't know who he is," she said. "I've never heard of him."

Nor had she ever heard of the Tiananmen protests.

Late last week, the wintry courtyard of a quiet Beijing residence was awash in white, the Chinese color of mourning. White chrysanthemums, white posters inked with black calligraphy, white corsages pinned on the lapels of ordinary Chinese who paid respects to disgraced Communist Party leader Zhao Ziyang. Dead at the age of 85, Zhao had spent 15 years under house arrest after opposing the regime's June 1989 crackdown in Tiananmen Square. One of the thousands of mourners was Dean Peng, an iconoclastic economist and democracy advocate who considers Zhao "China's Gorbachev." In a condolence book, he wrote, "We'll carry on the course you left behind; Democracy will come to China," then scribbled his name boldly. "Why should I be afraid?" Peng explained later. "Authorities should be afraid of me. The way they're suppressing the news just shows how afraid they are." He vowed to return over the weekend with a "big group" of sympathizers.

At this point, you might think you know where this story's going. The scene seems to evoke the passions that exploded the last time a popular but deposed party chief, Hu Yaobang, died; that ferment morphed into the 1989 protests. But here's a reality check: Peng's public feistiness was rare last week. Zhao's admirers are many, but most were afraid to visit the private memorial hall where plainclothes police scrutinized all comings and goings. Some dissidents who wanted to come were barred from leaving home. The only place in China to allow public mourning was Hong Kong, where legislators observed a moment of silence and 15,000 people held a candlelight vigil. Most mainland Chinese knew little of Zhao's death, thanks to an internal Communist Party directive that kept media reports down to a terse two-line notice. Among the millionsof educated urbanites who learned the news from the Web or word of mouth, veterans of '89 among them, most vented their sorrow for Zhao only in cyberspace.

Nobody expected the death of Zhao, seen as an icon of political reform, to trigger the sort of pro-democracy demonstrations that augured his downfall in 1989. The important question is why. The conventional wisdom is that China's intelligentsia today are apolitical and money-grubbing, more interested in jobs than democracy. The real answer is more complex. Due to economic reforms championed by Zhao and continued after his ouster, urban Chinese today have considerably more control over their lives than they did in 1989. They can choose their careers and where to live, buy cars and drive to Tibet, even compete in the "Miss Plastic Surgery" beauty contest if they want.

To a large extent, Chinese appreciate these personal, rather than political, liberties. According to a Gallup poll released last week, a majority of Chinese say they're "very" or "somewhat" satisfied with their lives and, perhaps most important, were remarkably optimistic as they looked forward to the next five years. When Wu'er Kaixi was a bratty 21-year-old student leader at Tiananmen, the government assigned graduates their jobs. He would have wound up an Education Ministry bureaucrat, or a teacher. Now, says the exile, who's a media commentator in Taiwan, Chinese kids have some say over their economic destiny. "They're not as frustrated as we were," says Wu'er Kaixi, 36. "They see hope."

The Internet also plays a role in diffusing anger, even as it serves as a sounding board for dissent. The government called former Beijing Normal University lecturer Liu Xiaobo a "black hand" behind the 1989 unrest; since then, he's spent nearly five years either in prison or in a labor camp, and he was briefly detained several weeks ago. He says the Internet has made life easier. To drum up a pro-democracy petition "in the '80s, you had to ride your bicycle a long, long way and even then you'd only get a few names on the petition," says Liu. "Now you just post it on the Internet and you get hundreds of thousands of names." One university professor in Beijing says so-called bulletin board systems, or BBSs, offer a safety valve that diminishes the likelihood of student unrest. "If students want to show their anger they'll go to the Internet. In 1989, the only public sphere was Tiananmen Square. Now the BBS is Tiananmen Square."

Which is not to say the aggrieved and dispossessed don't exist, or that they never take to the streets. Demonstrations erupt routinely in China, and the gap between the urban rich and rural poor is growing. But today's grievances focus largely on local bread-and-butter issues—lost jobs, excessive fees, inadequate pensions, illegal home demolitions. Even when protests are overtly political, they're not demanding Jeffersonian democracy.

In a scene that illustrates the shifts of the past 15 years, last Monday a group of middle-aged Chinese intellectuals gathered for a prescheduled reunion, some of them unaware that Zhao had died that morning. They were successful artists and literati who doubled as party cadres, publishers and university department heads—the "backbone of society" as one put it—all of whom had camped out as Tiananmen protesters in 1989. Someone mentioned that Zhao had died; chopsticks fell silent. Then the former demonstrators lifted their glasses to Zhao, before dumping them on the floor—another Chinese death ritual. "I wouldn't say we felt satisfied, but it was over," recalls a fortysomething property developer. "Frankly speaking, the life we're leading today has far surpassed the extent of freedom we imagined back then. In the history of China, I'm afraid, the people have never been so open and free. The Western world has no way of understanding this."

Authorities—who last week reiterated that the party's actions in 1989 were "correct"—are sure to remain tense. Police prepared tight surveillance in Tiananmen Square and for a memorial service planned at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery. Provincial protesters often gather in Beijing during March Parliament meetings. The June 4 anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre is always a time of heightened security and political emotion. Few Chinese are ready to risk a bloody repeat of those protests. But Zhao's death has shown that the regime's insecurities have not entirely disappeared.