Cambodia Travel Notes - Part 3 (Choeung Ek)

Part 2 was about the torture center with the code name of S-21 at Tuol Sleng. From David Chandler's Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison:

During 1977, when purges intenified, the facility at S-21 filled up, and so did the impromptu cemetery nearby. At some point in 1977 a Chinese graveyard near the hamlet of Choeung Ek, fifteen kilometers southwest of the capital, was put into service as a killing field, although important prisoners continued to be executed on the prison grounds. Located near a dormitory for Chinese economic experts, the site was equipped with electric power to illuminate the executions and to allow the guards from the prison to read and sign the rosters that accompanied prisoners to the site. This was where the prisonsers Nhem En saw were sent to be "smashed" or "discarded." After the site was discovered in 1980, it was transformed under Vietnamese guidance into a tourist site where even today scraps of bones and clothing can be found near the excavated burial pits.

To reach the Choeung Ek site, it is necessary to go down a bumpy country road with shacks, rice paddies and grazing cows by the side. There is no hint as to where this road leads to. Eventually, one reaches the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center.

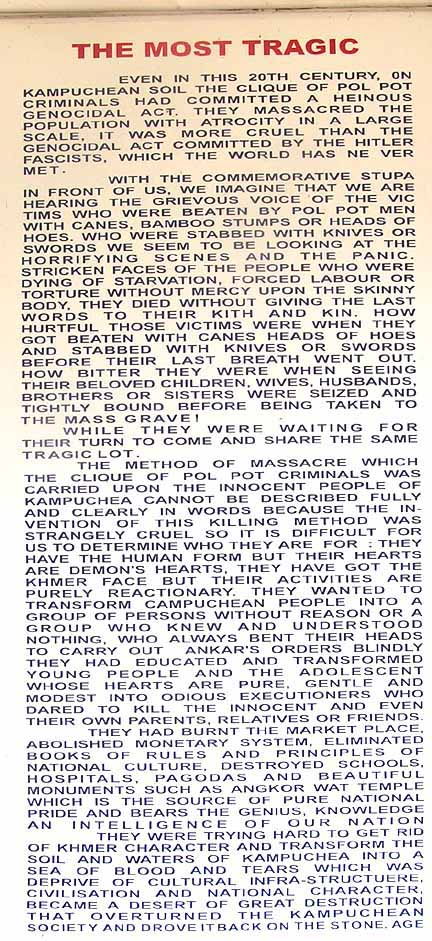

This is the detailed description given at the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center.

There is only one visible constructed building on the grounds of the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center. This is the stupa (=Buddhist memorial mound or pagoda).

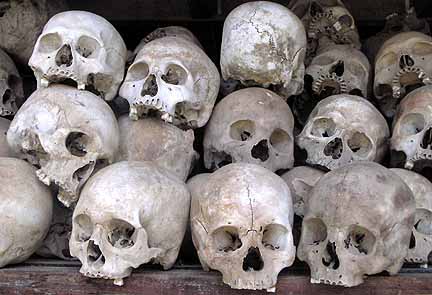

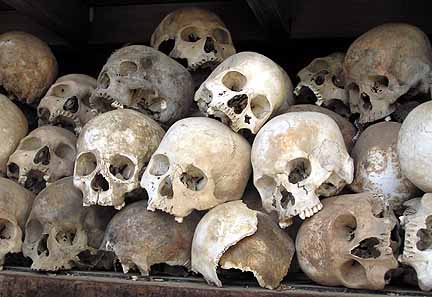

If you look inside the windows of the stupa, you will note that there are glass storage shelves. There are fifteen layers of these shelves.

If you enter the stupa, you can look at the contents of the shelves. The glass windows can be opened and you can reach in and touch the contents. Not many people can bear to do that. At this point in history, they cannot physically hurt, but psychically they can touch and hurt tremendously.

All these skulls were collected from the killing fields on the grounds of Choeung Ek.

Outside the stupa is an open space. The notice below is posted at the entrance: 86 mass graves containing 8,985 victims. There are in fact 129 graves altogether at Choeung Ek of which only 86 have been excavated and examined so far. Choeung Ek is not the only killing site in Cambodia, as there are hundreds more around the country. However, this one is the largest identified so far.

On the grounds, there is a traditional Chinese tomb of a couple buried together and erected by their children. As mentioned above, this site was originally a cemetery for the Chinese living in Cambodia.

What do the killing fields look like today? If you look across, this is just a series of shallow ditches about two or three feet deep. Otherwise, there is nothing especially eye-catching about them. Historically, when the killing fields were discovered, they also looked like this. They were constructed by digging a grave about 3 meters deep, and then several hundred bodies were tossed in and spread out. The bodies were then covered by a thin layer of earth. After the Khmer Rourge were expelled, these fields were excavated, the skulls were taken out and placed in the stupa, and then the fields were refilled. This is how they came to look like this today.

If you look hard enough, there are urns on which some human bones were collected, and some bones and rags can still be found at spots. Otherwise, this is a serene spot in the countryside.

The preceding descriptoin was according to the script delivered by the local tour guide. Again, the imagination fails, compared to the following photos taken at the S-21 museum of the excavation process.

From David Chandler's Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison:

Him Huy's description of the killings at Choeung Ek, repeated with variations on several interviews, is the only firsthand account that we have so far ... Normally, "once a month, or every three weeks, two or three trucks" would go from S-21 to Choeung Ek. Each truck held three or four guards and twenty to thirty "frightened, silent" prisoners. When the trucks arrived at the site, Huy recalls, the prisoners assembled in a small building where their names were verified against an execution list prepared beforehand by Suos Thi, the head of the documentation sectoin. A few execution lists of this kind survive. Prisoners were then led in small groups to ditches and pits that had been dug earlier by workers stationed permanently at Choeung Ek. Him Huy continued, with an almost clinical detachment:

They were ordered to kneel down at the edge of the hole. Their hands were tied behind them. They were beaten on the neck with an iron ox-cart axle, sometimes with one blow, sometimes with two ... Ho inspected the killings, and I recorded the names. We took names back to Suos Thi. There could not be any missing names.

Him Huy remembers prisoners crying out, "Please don't kill me!" and "Oeuy" (my beloved).

Here is the grave with the largest number of victims found (=450). The sight today does not convey the horror.

The following photos are for some paintings drawn by a survivor that were exhibited at the S-21 museum.

You may think that once you have seen one grave, you have seen them all. But there are in fact sub-classifications within the graves. The following one is for 166 victims without heads. There is no hint as to where the heads had been taken.

How were the heads sawed off? The local tour guide pointed to the banyan tree and asked us to feel the blade of the leaf branch. I touched it and, yes, it would be strong enough to saw off a few heads. But I would never imagine that this is what it would be used for.

In this next grave, there were more than 100 bodies of children and women, most of whom were naked.

How did they kill babies? They were picked up and smashed against this tree. If not, they were bayoneted.

From David Chandler's Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison:

When we deal with the culture of S-21, it is tempting to rush to judgment, but it is also easy to judge the interrogators, guards, or executioners too severely. They could disobey orders only on pain of death. Without similiar experiences, temptations, and pressures it is impossible for any of us to say how we might have behaved had we been interrogators ourselves, locked in a cell facing a helpless and devalued "enemy" alongside a pair of colleagues, either of whom might report us to the authorities for failing to inflict torture or for "counterrevolutionary" hesitation. Similarly, we cannot say what we would have done at Choeung Ek if a superior gave us an iron bar with which to smash the skull of a kneeling victim.

I could give you an answer as to what I would do. But that is hypothetical, and I will never know for sure until that true moment arrives. And I hope that moment never arrives.

In my overall impressions of Cambodia in Part 1, I wrote:

My pre-existing ideas of Cambodia came from William Shawcross' book Sideshow about Kissinger-Nixon's secret war, the 1984 movie The Killing Fields and some postcard images of Angkor Wat. To be quite honest, it is not much to speak of.

One of the long-lasting effects of having watched The Killing Fields was a visceral reaction with respect to a certain piece of music. In the movie, the Sydney Schanberg character had left Cambodia and was working at home with the Puccini aria Nessun Dorma playing in the background until he realized that he would never have peace of mind. From there on, I could never listen that aria without a shiver. Is it conscionable for a member of the First World to enjoy the best cultural products while terrible suffering continues to exist in this world?

There is no right or wrong answer to that question.