The Shanwei (Dongzhou) Incident

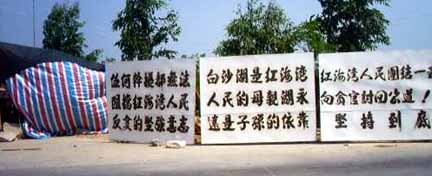

The following is an illustration of the level of details in coverage by English- and Chinese-language media of the same event. The listing is done in order of increasing details within the English-language reports, and then the translated Chinese-reports appear below. I have listed only the sections pertaining to the incident itself and omitted background information. There is a set of photographs from the scene earlier in October.

This is not intended as criticism of any of the media. Rather, the point is used to show how the media operate with different levels of space, access to information and journalistic standards for reportability.

Please note how almost everybody else had to rely on the Radio Free Asia report. The Shanwei incident has been going on for more than five months and Radio Free Asia was covering it while nobody else paid much attention. Then when the violence broke out, Radio Free Asia already had the background information as well as sources on the ground. It was a lot harder for others to catch up. You can see that they tried (e.g. calling up the police and being given no information). Please also note that some services felt that it necessary to qualify Radio Free Asia as "US-government supported" or at least as "U.S. broadcaster."

The Epoch Times item at the bottom stands out from the rest. If everyone else refers to several hundred or more than 1,000 police officers, they say 2,000 to 3,000. If everybody else refers to three dead with names given, they say more than ten dead instead. If everybody else refers to tear gas canisters fired at close quarters as the cause of death, they say that the armed police sprayed the villagers with submachine gunfire instead.

(BBC News) December 7, 2005.

Chinese armed police are reported to have opened fire on protesters in the southern province of Guangdong, shooting dead at least two people. Witnesses told US broadcaster Radio Free Asia the incident happened after hundreds of police tried to disperse up to 1,000 demonstrators near Shanwei.

(Kyodo News) December 7, 2005.

At least two people have died in China's southern province of Guangdong after police fired on villagers protesting inadequate compensation for land taken away for wind-power plant construction, Radio Free Asia reported Wednesday. By Tuesday evening, two men had died in a Donghua village hospital near the port city of Shanwei after being shot the previous day by riot police, the U.S.-based radio service said, quoting a hospital official. But the report also quoted a Donghua villager as saying a total of four villagers have been killed in the incident, with many others suffering gunshot wounds.

(Reuters AlertNet) December 7, 2005.

Chinese police opened fire on villagers protesting against the lack of compensation for land lost to a new wind farm in the southern province of Guangdong, local officials and residents said on Wednesday. U.S. broadcaster Radio Free Asia and residents said at least two villagers were killed in the assault after riot police moved into the area on Monday to quell the unrest in the Guangdong village of Dongzhou.

"In the beginning, there were about 100 to 200 villagers protesting and gradually the number got bigger as more and more people came to watch," said an official surnamed Chen in the nearby city of Shanwei. "The police didn't bring guns at first, but some villagers used pipe bombs to attack the police, so the police station sent more police with guns to the scene," he said.

Police detained three representatives from Dongzhou on Tuesday, which prompted thousands more to come and demand their release, the Radio Free Asia report said, putting the number involved in the demonstration at 10,000.

(Associated Press via The Standard) December 7, 2005.

Police opened fire on villagers protesting the construction of a wind-power plant in Guangdong, leaving at least two people dead, a news report said Wednesday. Local police and other officials contacted by telephone in Dongzhou, a village in the southern coastal city of Shanwei, refused to comment. "That's something between the villagers and local government. We are just doing our project and we're not clear about what's going on there," said a spokeswoman for Guangdong Red Bay Generation, a company building a coal-fired power plant nearby. She gave only her surname, Wang.

US-government supported Radio Free Asia, citing witnesses and hospital staff, said at least two people died and an unknown number of others were injured when police began shooting late Tuesday on a crowd of "thousands" of villagers....

Local police and government officials declined to provide details and either denied or refused to say whether police opened fire. "The masses caused some obstruction yesterday. We are dealing with it and trying to resolve it," said an official at the neighborhood Red Bay district police station, refusing to say whether police opened fire.

(AFX via Forbes) December 7, 2005.

Soldiers in southern China's Guangdong province killed four people when they opened fire on more than 1,000 villagers protesting the construction of a power plant, residents said.

The clash happened yesterday evening in Dongzhou village in Shanwei city when hundreds of officers from the People's Armed Police -- a unit of the People's Liberation Army -- were sent in to disperse the villagers, residents told Agence France-Presse.

'The People's Armed Police entered the village, they opened fire and shot to death four people,' said a villager by telephone. 'Two died in a local hospital and two were taken to a hospital in Shanwei's urban center, but they died too,' he said before his phone appeared to be cut off.

A teacher at the Dongzhou Middle School said he did not see the incident because he lived outside the village but learned about it when he arrived at work today. 'It's mainly because of land dispute. Compensation was one of the problems,' said the teacher, who declined to be named.

When contacted by Agence France-Presse, Shanwei city police and city government officials said they did not have any knowledge of the incident and declined to comment further.

(South China Morning Post) December 7, 2005.

Eight villagers were reportedly shot dead by Guangdong police on Tuesday when officers were sent in to break up a protest connected to a land requisition dispute.

Police and government officials in Shanwei - which oversees Dongzhou village - refused to comment yesterday despite repeated attempts for confirmation. "It's not a simple case, because in such a harmonious society, our armed police won't presume to open fire on villagers," a spokesman for Shanwei city government said. Officials from the Shanwei Public Security Bureau said they were "not clear" about the incident.

But a villager contacted yesterday said his brother, Lin Yutui , 26, was among the victims and was shot by police when he went to join the protesters. "He died at the scene immediately because one bullet hit his heart and another his pelvis," said the villager, who declined to give his full name. The villager claimed that eight protesters were killed, but this could not be independently confirmed. According to the man, some of the villagers were still being treated in hospital. He claimed some of the police officers who had taken part in the crackdown had come from neighbouring cities of Lufeng and Luhe.

(AFP via Aljazeera.net) December 7, 2005.

Soldiers in southern China's Guangdong province have killed four people after firing on more than 1000 villagers protesting against the construction of a power plant. The clash happened on Tuesday evening in Dongzhou village in Shanwei city when hundreds of officers from the People's Armed Police - a unit of the People's Liberation Army - were sent in to disperse the villagers, residents said on Wednesday.

"The People's Armed Police entered the village, they opened fire and shot to death four people," said a villager by telephone. "Two died in a local hospital and two were taken to a hospital in Shanwei's urban centre, but they died, too," he said before his phone appeared to be cut off.

A teacher at the Dongzhou Middle School said he did not see the incident because he lived outside the village, but learned about it when he arrived at work earlier in the day. "It's mainly because of land dispute. Compensation was one of the problems," said the teacher, who declined to be named.According to locals interviewed by the US-based Radio Free Asia, the villagers had been demanding that the government should compensate them fairly for building the power plant, but their requests were denied. Tensions have escalated for many months and came to a climax on Tuesday, according to villagers and protesters quoted by Radio Free Asia.

"They were firing shots. But they were afraid to move in. We had blocked the roads with water pipes, gasoline and detonators," a villager who called RFA late on Tuesday said. Another villager Radio Free Asia quoted said "many" villagers had suffered shotgun wounds. "I don't know what kind of guns. I just know they were using real bullets on us. No policemen were wounded," the villager added.

The radio station said it had confirmed that two people had been killed, and quoted villagers as saying four had died....

Shanwei city police and city government officials said they did not have any knowledge of the incident and declined to comment.

(Radio Free Asia) December 7, 2005.

At least two villagers in China's southern province of Guangdong have died after police fired on a crowd protesting the construction of a wind power plant, Radio Free Asia (RFA) reports. Witnesses told RFA's Mandarin service that by 9:30 p.m. Tuesday, villagers Jiang Hu and Jiang Guanji had died in the local hospital while a third, identified as Tang Daxiang, was receiving emergency treatment. Dongzhou Hospital authorities near the city of Shanwei confirmed two deaths and one wounded undergoing treatment, but they declined to give names.

"At least four villagers have died," another villager said at approximately 11:30 p.m. "There is a dead body on the street yet to be retrieved. Many are wounded by gunshots. I don't know what kind of guns. I just know they were using real bullets on us. No policemen were wounded."

"The hospital has become a virtual funeral hall with family members of the dead crying," one villager told reporter Ding Xiao. "They were bleeding. One was hit in the head, one in the foot, and one in the torso. They have been rushed to Dongzhou Hospital. We have prepared detonators. We're ready to fight," another said.

According to several eyewitness accounts, hundreds of riot police moved into the site of the wind power plant Monday after a long-simmering dispute over how much villagers should be paid for land slated to become a wind-power plant. Around midday Tuesday, three representatives from Dongzhou village went to the site to see what was happening. The three villagers were immediately detained, witnesses said.

Shortly after 5 p.m., thousands of villagers showed up at the site of the plant and demanded the release of the three representatives, they said. Police stationed inside the power plant fired tear gas at the crowd but caused no serious injuries. Later Tuesday, authorities dispatched several hundred more riot police to the site of the plant but they were stopped outside Dongzhou village by villagers.

"We are really scared. We need your help. The riot police are at the entrance of our village. There are several hundred of them, between 400 and 500," one villager said in an interview that was cut off several times. "They were firing shots. But they were afraid to move in. We had blocked the roads with water pipes, gasoline and detonators," another villager said. "And there were about 10,000 villagers there. We tried calling the central government several times for help. But all we got was answering machines."

Riot police have now crashed through roadblocks set up by villagers and dismantled their tents near the power plant. Villagers have retreated back to Dongzhou village, they said. Li Min, deputy mayor of Shanwei and chief of public security, asked to comment by phone, said only, "I don't know" and hung up. Guangdong provincial public security offices and the Guangdong provincial government went unanswered. A duty officer at the Dongzhou police station said, "I am not familiar with the situation." Asked to confirm that two villagers had died, he said, "There is no such thing," and hung up.

(Wen Wei Po) December 7, 2005.

[in translation]

Our reporter called up the Shanwei City propaganda department to ask for confirmation on the clash between police and citizens in Honghaiwan. The relevant person said that the nature of the incident is still undetermined . The Shanwei City has prepared a report and will forward the information to the provincial govenment. All release of information concerning that incident will be made by the Guangdong provincial propaganda department.

(Ming Pao) December 7, 2005.

[in translation]

A serious clash between police and citizens occurred in Shanwei City (Guangdong province). Several thousand villagers in the Honghaiwan district of Shanwei protested the loss of the compensation money for building a local electricity plant. On the evening before yesterday (December 6), they gathered in front of the power plant to prevent work. At the time, the authorities sent in more than a thousand police to clear the scene. The sides clashed and the police fired tear gas canisters to disperse the villagers. As of now, the police is still sealing off the village to prevent people from entering or leaving. When one newspaper called up the Shanwei police, they said that they have not heard of this incident.

According to a villager named Chen, the government had requisitioned a large plot of land area including hills, farmland and the White Sand Lake for the purpose of building a large power plant The villagers did not receive reasonable compensation, and the villagers who depend on the sea to earn their living have nowhere to do. So the villagers took turns to protest outside the Shanwei power plant. This affair has been going on for more than 5 months.

According to the villagers, on the evening before yesterday, the government sent more than one thousand anti-riot armed police officers to clear the scene. Several thousand villagers from the nearby Zhongxiuwei village and Shigu village heard the news and came over to help. The police and the citizens faced off against each other. The demonstrators used water pipes and other material to block the road. They also prepared gasoline and home-made fire bombs, so tht the armed police cannot advance.

At about 7pm in the evening, the police took action. They used tear gas to disperse the demonstrators. Three villagers were injured seriously in the head with tear gas canisters and died after being brought to the hospital. Several dozens more people were injured and had to go to the hospital. By yesterday night, the local villagers said that 5 persons died from injuries and more than a dozen disappeared.

Eyewitnesses said that the armed police charged many times into the crowd and used their truncheons to hint the villagers. The villagers used shoulder poles, farm implements and home-made fire bombs to fight with the armed police. Some armed police fired the tear gas canisters right at the demonstrators in close range, thus causing the injuries and deaths.

(Epoch Times via Boxun) December 7, 2005.

[in translation]

According to the latest news from Epoch Times, the Guangdong Shanwei government sent out 2,000-3,000 armed police and anti-riot police into Dongzhou village in Honghaiwan. They used submachine guns to rake the villagers and released tear gas to disperse the villagers. According to local villagers, the police killed more than 10 villagers and arrested two village representatives.

According to information provided by the villagers, "At the time, we know that more than 10 villagers are dead and 40-50 are wounded The wounded have been sent to neighboring hospitals. The more serious injured persons have been sent to Shantou Hospital. According to reports, some of the wounded are in criticial condition. The villagers were allowed to take only two bodies back home. The other bodies have been removed by car. At the time, it was very chaotic at the scene. The villagers on duty left quickly, or else the casualties would be higher. Most of the dead are between 20 to 30 years old ... !

The following is an earlier report:

According to Epoch Times' Xu Poheng, about 3,000 armed police and anti-riot police entered Honghaiwan in Guangdong's Shanwei City at 5pm on December 6. They clashed with villagers trying to defend their land. The armed police and the anti-riot police even shot at the villagers. Three persons who instantly shot to death and another 6 to 7 were wounded. The dead people are between 20 to more than 30 years old. The wounded have been sent for treatment at Shantou's Yihui Hospital. The armed police and anti-riot police fired at the villagers, and also released tear gas to drive the villagers away. The reporter is from Dongzhouhang village, where the people have been forced to retreat back into their own village.

(Associated Press)

(Boxun) October 9, 2005.

Follow-up reports (in chronological order). The usual warning applies -- DO NOT BELIEVE EVERYTHING THAT YOU READ. There is a simple test -- these reports cannot be ALL true (that is, the number dead cannot be three and "more than 70" at the same time.

(Washington Post) Police Open Fire on Rioting Farmers, Fishermen in China. By Edward Cody. December 8, 2005.

Paramilitary police and anti-riot units here have opened fire with pistols and automatic rifles for the past two nights on rioting farmers and fishermen who have attacked them with gasoline bombs and explosive charges, according to residents of this small coastal village.

The sustained volleys of gunfire, unprecedented in a wave of peasant uprisings over the past two years in China, have killed between 10 and 20 villagers and injured more, residents said. The count was uncertain, they said, because a number of villagers have disappeared and it is not known for sure whether they were killed, wounded or driven into hiding.

The tough response by black-clad riot troops and People's Armed Police in camouflage fatigues deviated sharply from previous government tactics against the spreading unrest in Chinese villages and industrial suburbs. As far as is known, previous riots have all been put down with heavy use of truncheons and teargas, but without firearms.

This time, according to a villager who heard and saw what happened, police responded to the launching of explosives by firing repeatedly "very rapid bursts of gunfire" over a period of several hours Tuesday and Wednesday nights. Some villagers reported seeing the People's Armed Police carrying AK-47 assault rifles, one of the Chinese military's standard-issue weapons. There were no reports of violence Thursday night.

The villagers who rose up against land confiscations in Dongzhou, a community of 10,000 residents 14 miles southeast of Shanwei city, in Guangdong province near Hong Kong, also opened a new chapter -- the use of the homemade bottle bombs and explosive charges that local fishermen normally use to stun fish in the adjacent South China Sea. In previous riots, attacks against police were limited to pelting them with stones and bricks or setting fire to official vehicles.

The Communist Party and city administration of Shanwei, which has jurisdiction over Dongzhou, held all-day meetings Thursday on the violence, officials said. The city spokesman, however, refused to discuss what happened in the village and also declined to give his name. He said only that local authorities were taking the crisis seriously.

There likewise was no public response from the Guangdong provincial Communist Party and government, which have been hit by several long-running and violent confrontations over land confiscations during the past year. As was the case in most previous unrest, the government-censored press and television has not reported on the violence in Dongzhou.

Police set up a roadblock at the edge of the village, blocking most vehicles from entering or leaving, and white Public Security vehicles patrolled the main road linking Dongzhou with Shanwei. Pedestrians and motorcycles were allowed to pass in and out of the village, however, and buses waited for passengers just outside the checkpoint.

About 700 yards down the main street, about 100 villagers glared Thursday afternoon at a force of approximately 300 riot police, wearing helmets and carrying shields and batons, while an officer using an electric loudspeaker urged residents repeatedly to stay in their homes.

"This has nothing to do with you," he blared. "Return to your houses."

The long-simmering conflict in Dongzhou arose over disputed confiscations and what farmers here said were inadequate compensation payments. Authorities exercising the equivalent of eminent domain seized farmers' fields to build a wind-driven electric generating plant on a hillside overlooking the village. The plant would be part of a $700 million electricity development project to supply the growing power needs of Shanwei and surrounding towns and villages.

Villagers, contacted by telephone, complained that the compensation was inadequate. Moreover, they charged, the power plant would spoil fishing in Baisha Lake, a tidal inlet just below the hill on which villagers rely for seafood.

The confrontation was typical of the tension across China between economic development, which runs about 9 percent a year, and farmers' desire to retain the land that they regard as security for their families. The tension is particularly acute here in Guangdong province and the Pearl River Delta, where during the past two decades of economic liberalization, factories and dormitories have steadily eaten away at the rice paddies, corn fields and fruit orchards that used to flourish in the warm, wet climate.

For most of this year, Dongzhou villagers have been protesting on and off against the power plant project, originally scheduled to be finished in 2007 but now delayed. One protest leader, surnamed Huang, was arrested in July.

"It is illegal to impede the progress of a key infrastructure project," a Shanwei spokesman, Li Min, told Radio Free Asia then. "As for whether the compensation is reasonable, it was in line with the usual standards."

The villagers, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, said the current round of violence was set off when authorities arrested three village leaders who had gone to the hillside plant site Tuesday afternoon to lodge a complaint. Before long, they said, several thousand villagers gathered on the hilltop to demand their release.

Those villagers were dispersed by volleys of teargas fired by police, residents said. But shortly afterward, authorities dispatched between 400 and 500 more riot police into the village as reinforcements, the residents said. That contingent was met by several thousand angry villagers, they added, and police again resorted to teargas about dusk. This time, however, some villagers reacted by pelting police with the explosives, according to witnesses, and the police responded with sustained pistol and automatic weapons fire over the following three hours.

A similar confrontation occurred Wednesday evening on the main village road, leading to more attacks with gasoline bombs and several more hours of shooting, the villagers said. "The police kept on shooting until they drove away all the villagers," said a witness.

In the absence of official information from the government or Dongzhou hospital, reports flew from family to family of villagers killed, bodies burned and relatives unable to retrieve their slain loved ones left lying in the street. Some said 20 villagers were killed each night; others said the total was 14.

"I saw the bodies lying there," said one witness to Tuesday night's violence. "The family members were afraid to go and get them."

One villager, Liu Yujing, 31, said his younger brother, Liu Yudui, 26, was hit by two rounds, one in the heart and one in the bladder, immediately after he stepped outside the family home to see what was going on in the street Tuesday evening. "He died before we could get him to the hospital," Liu said.

(Epoch Times via Boxun) December 8, 2005.

[in translation]

In an 11:30pm interview with our reporter, a villager said: "Yesterday, people were busy taking care of things. We were trying to count the number of dead and missing. We have now found six bodies and they are at the Dongzhou Hospital. A severely injured villager has died in the hospital. There are 30 to 40 people missing. It is not known whether they died or fled. We don't know. We heard that there are more bodies on the hill, but no one can go in there. The main representatives of the village are in great peril. Right now, it is no longer about arresting you and sending you to jail. It is shoot on sight. Yesterday afternoon, a village was shot dead right at the scene."

Some villager offered an exact count by claiming to know that 33 villagers have been shot to death, and more than 20 missing. Most of them are young men in the 20's. There was a young man who works in another province but came back to Dongzhou village to get married. On December 6, he went to check out what was happening in front of the power plant and he was killed right at the scene.

The villager also said that the government is trying to destroy the evidence. On the night of the shooting, some corpses were cremated. They took the bodies to the seaside. When the villagers wanted to retrieve the bodies, they were sopped. The scene in front of the power plant at which the armed police and the anti-riot police raked the villagers with gunfire, the villagers were only able to retrieve some empty bullet shells. A villager told the reporter that the authorities used 30 boxes of bullets on that day.

There are still several thousand armed police and police officers in front of the village. The authorities also sent out a tank and the tank gun is aimed at the village. According to the villagers, after the shooting on December 6, fully armed policemen came on both December 7 and 8 to arrest people. The unarmed villagers are very frightened.

A young male villager cried to the reporter over the telephone. He was afraid of being killed and wanted to get out of Dongzhou town. But the armed police officers have blocked the village entrance. The police checked people's ID's and all Dongzhou residents are turned back and cannot leave. He also said that a Hong Kong resident who came back to attend a wedding banquet was also stuck in the village.

On the day of the shooting, the police falsely claimed that they were entering the village to investigate a white powder (heroin) case. They wanted to arrest the three rights representatives of the village. At the moment, there are posters for the arrest of the three village representatives for "smoking white powder (吸白粉)."

During an interview just after 5pm on December 8, a female villager cried out in fear: "They have just come in again" and "Four armed police officers just entered the village to arrest people." And then the telephone was cut off.

The Shanwei television news program reported that the villagers started shooting first. A villager angrily said: "Which citizen has a gun? The guns are all in their hands!"

...

(The Guardian) Chinese militia open fire on demonstrators opposing coal plant. By Jonathan Watts. December 9, 2005.

In one of the most violent confrontations in a wave of recent rural unrest, Chinese paramilitary forces have shot and killed at least one man and injured more than a dozen others during protests against a power plant in Guangdong, local residents said yesterday.

Police reportedly used tear gas on a crowd of several thousand demonstrators, some of whom were said to have been throwing Molotov cocktails and pipe bombs. The death toll from the riot, in Dongzhou village on Tuesday evening, could rise. Local authorities refused to provide details of casualties but reports in the Hong Kong and overseas media suggest up to 15 people may have been killed.

A witness, who only gave her surname, Huang, told the Guardian that a former schoolmate, Lin Yutui, was among the dead. "We didn't expect the police would hurt us so when they fired warning shots in the air, nobody dispersed. Even when they used tear gas, people wouldn't withdraw. So then they used real bullets. I saw people get shot."

After her father was hit in the face by a tear-gas canister, Huang took him to a clinic where she described scenes of grief and chaos. She said the head of the clinic was imploring the biggest nearby hospital, in Shanwei, to send help. A member of staff at the Shanwei municipal hospital confirmed that wounded people had been brought in on Tuesday.

Several Hong Kong media groups said the deaths and wounds were caused by tear-gas canisters being fired at close range. But Mr Lin's family was quoted as telling the South China Morning Post that he had been killed instantly by two bullets, one to the heart and one to the pelvis.

Another witness, Liu, said: "I guess there were about 10-20,000 locals and more than 1,000 police, including militia. The police used rubber bullets first, then villagers threw petrol bombs and pipe bombs at them, so the police used some kind of machine gun ... I heard from others that three people were killed."

Branches of the public security bureau were not answering phones, and the mainland media were ordered not to report the incident.

The level of the violence this week had been unusual, but protests are becoming common. According to central government, 3.6 million people took part in 74,000 "mass incidents" last year, an increase of more than 20% on 2003. As in Dongzhou, most of these demonstrations were about property and pollution.

Dongzhou's villagers oppose the construction of a coal-fired power plant partly on land reclaimed from the nearby Baisha saltwater lake. Although construction of the 6.2bn yuan (£440m) development began in 2003, residents say they have not been compensated for lost income and land or the likely deterioration in the air and water quality. For the past two months, they have blocked the road into the construction site.

Tuesday's violent escalation was sparked by the arrest of the campaign's leaders. According to the AFP news agency, hundreds of officers from the People's Armed Police, a unit of the People's Liberation Army, attended the scene. The developer denied any involvement.

(New York Times) 20 Reported Killed as Chinese Unrest Escalates. By Howard French. December 9, 2005.

Residents of a fishing village near Hong Kong said that as many as 20 people had been killed by paramilitary police in an unusually violent clash that marked an escalation in the widespread social protests that have roiled the Chinese countryside. Villagers said that as many as 50 other residents remain unaccounted for since the shooting. It is the largest known use of force by security forces against ordinary citizens since the killings around Tiananmen Square in 1989. That death toll remains unknown, but is estimated to be in the hundreds.

The violence began after dark in the town of Dongzhou on Tuesday evening. Terrified residents said their hamlet has remained occupied by thousands of security forces, who have blocked off all access roads and are reportedly arresting residents who attempt to leave the area in the wake of the heavily armed assault.

"From about 7 p.m. the police started firing tear gas into the crowd, but this failed to scare people," said a resident who gave his name only as Li and claimed to have been at the scene, where a relative of his was killed. "Later, we heard more than 10 explosions, and thought they were just detonators, so nobody was scared. At about 8 p.m. they started using guns, shooting bullets into the ground, but not really targeting anybody.

"Finally, at about 10 p.m. they started killing people."

The use of live ammunition to put down a protest is almost unheard of in China, where the authorities have come to rely on rapid deployment of huge numbers of security forces, tear gas, water cannons and other non-lethal measures. But Chinese authorities have become increasingly nervous in recent months over the proliferation of demonstrations across the countryside, particularly in heavily industrialized eastern provinces like Guangdong, Zhejiang and Jiansu. By the government's tally there were 74,000 riots or other significant public disturbances in 2004, a big jump from previous years.

The villagers in Dongzhou said their dispute with the authorities had begun with a conflict over plans by a power company to build a coal-fired generator in their area, which they feared would cause heavy pollution. Farmers said they had not been compensated for the use of the land for the plant. Others said plans to reclaim land by filling in a local bay as part of the power plant project were unacceptable because people have made their livelihoods there as fishermen for generations. Already, villagers complained, work crews have been blasting a nearby mountainside for rubble for the landfill.

A small group of villagers was delegated to complain to the authorities about the plant in July, but they were arrested, infuriating other residents and encouraging others to join the protest movement. On Dec. 6, while villagers were mounting a sit-in demonstration, police made a number of arrests, bringing lots of people out into the streets, where they managed to detain several officers. In response, hundreds of law enforcement agents were rushed to the scene. Everybody, young and old, "went out to watch," said one man who claimed his cousin had been killed by a police officer's bullet in the forehead. "We didn't expect they were so evil. The farmers had no means to resist them."

Early reports from the village said the police opened fire only after villagers began throwing homemade bombs and other missiles, but villagers reached by telephone today denied this, saying that a few farmers had launched ordinary fireworks at the police as part of their protest. "Those were not bombs, they were fireworks, the kind that fly up into the sky," said one witness reached by telephone. "The organizers didn't have any money, so someone bought fireworks and placed them there. At the moment the trouble started many of the demonstrators were holding them, and of those who held fireworks, almost everyone was killed."

Other witnesses estimated that 10 people were killed immediately in the first volley of automatic gunfire. "I live not far from the scene, and I was running as fast as I could," said one witness, who declined to give his name. "I dragged one of the people they killed, a man in his 30's who was shot in his chest. Initially I thought he might survive, because he was still breathing, but he was panting heavily, and as soon as I pulled him aside, he died."

The witness said that he, too, had come under fire when the police saw him coming to the aid of the dying man. The Chinese government has yet to issue a statement about the incident, nor has it been reported in the state media. Reached by telephone, an official in the city of Shanwei, which has jurisdiction over the village, said, "Yes, there was an incident, but we don't know the details." The official said an official announcement would be made on Saturday.

Villagers said that in addition to the regular security forces, the authorities had enlisted thugs from local organized crime groups to help put down the demonstration. "They had knives and sticks in their hands, and they were two or three layers thick, lining the road," one man said. "They stood in front of the armed police, and when the tear gas was launched, the thugs were all ducking."

Like the Dongzhou incident itself, most of the thousands of riots and public disturbances recorded in China this year have involved environmental, property rights and land use issues. Among other problems, in trying to come to grips with the growing rural unrest, the Chinese government is wrestling with a yawning gap in incomes between farmers and urban dwellers, and rampant corruption in local government, where unaccountable officials deal away communal property rights, often for their own profit.

Finally, mobile telephone technology has made it easier for people in rural China to organize, communicating news to one another by short messages, and increasingly allowing them to stay in touch with members of non-governmental organizations in big cities who are eager to advise them or provide legal help.

Over the last three days, residents of the village say that other than people looking for their missing relatives, few people have dared go outside. Meanwhile, the police and other security forces have reportedly combed the village house by house, looking for leaders of the demonstration and making arrests.

Residents said that after the villagers' demonstration was suppressed a senior Communist Party official came to the hamlet from the nearby city of Shanwei and addressed residents with a megaphone. "Shanwei and Dongzhou are still good friends," the party official said. "We're not here against you. We are here to make the construction of the Red Sea Bay better. Later, the official reportedly told visitors, "all of the families who have people who died must send a representative to the police for a solution."

Today, a group of 100 or so bereaved villagers gathered at a bridge leading into the town, briefly blocking access to security forces hoisting a white banner whose black-ink characters read: "The dead suffered a wrong. Uphold justice."

(Associated Press) Chinese Village Surrounded After Shootings. By Audra Ang. December 9, 2005.

Hundreds of riot police armed with guns and shields have surrounded and sealed off a southern Chinese village where authorities fatally shot demonstrators this week, villagers said Friday. Although riot police often use tear gas and truncheons to disperse demonstrators, it is extremely rare for security forces to fire into a crowd — as they did in putting down pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989 near Tiananmen Square. Hundreds, if not thousands, were killed.

During the demonstration Tuesday in Dongzhou, a village in Guangdong province, thousands of people gathered to protest the amount of money offered by the government as compensation for land to be used in the construction of a wind power plant. Police started firing into the crowd and killed several people, mostly men, villagers reached by telephone said Friday. The death toll ranged from two to 10, they said, and many remained missing.

State media have not mentioned the incident and both provincial and local governments have repeatedly refused to comment. This is typical in China, where the ruling Communist Party controls the media and lower-level authorities are leery of releasing information without permission from the central government.

All the villagers said they were nervous and scared, and most did not want to be identified for fear of retribution. One man said the situation was still "tumultuous."

A 14-year-old girl said a local official visited the village Friday and called the shootings "a misunderstanding." "He said he hoped it wouldn't become a big issue," the girl said by telephone. "This is not a misunderstanding. I am afraid. I haven't been to school in days." She added: "Come save us."

Another villager said there were at least 10 deaths. "The riot police are gathered outside our village. We've been surrounded," she said, sobbing. "Most of the police are armed. We dare not go out of our home." "We are not allowed to buy food outside the village. They asked the nearby villagers not to sell us goods," the woman said. "The government did not give us proper compensation for using our land to build the development zone and plants. Now they come and shoot us. I don't know what to say."

One woman said an additional 20 people were wounded. "They gathered because their land was taken away and they were not given compensation," she said. "The police thought they wanted to make trouble and started shooting." She said there were several hundred police with guns in the roads outside the village Friday. "I'm afraid of dying. People have already died."

The number of protests in China's vast, poverty-stricken countryside has risen in recent months as anger comes to a head over corruption, land seizures and a yawning wealth gap that experts say now threatens social stability. The government says about 70,000 such conflicts occurred last year, although many more are believed to go unreported.

...Authorities in Dongzhou were trying to find the leaders of Tuesday's demonstration, a villager said. The man said the bodies of some of the shooting victims "are just lying there." "Why did they shoot our villagers?" he asked. "They are crazy!"

(Reuters AlertNet) Chaos in south China village after clashes. By Lindsay Beck and Ben Blanchard. December 9, 2005.

Armed police have sealed off a village in southern China after violent clashes with residents that rights group Amnesty International said marked the first time Chinese police had fired on protesters since 1989. Residents said riot police had opened fire on Tuesday on protesters in the village of Dongzhou in Guangdong province after they moved in to quell demonstrations over lack of compensation for land lost to a wind power plant. Estimates from residents and rights groups put the number of dead between two and 20.

"Now the authorities are coming to the village to detain people," said one villager, adding his brother was among those shot dead during the demonstrations. "My parents and my sister-in-law are kneeling in front of the house to ask the government officials to explain the killing," he said in a telephone interview. He put the number of dead at more than 10.

...The resident said police were chasing away family members who tried to claim the bodies of those who were killed, describing the scene as "chaos" and pleading for help. "Please send somebody to help us," he said. Noise in the background was so loud it was difficult to hear.

...

Residents said there were thousands of armed police in the area, blocking roads and detaining those suspected of involvement in the protests. "A lot of families have moved away from the village. We are all very scared. At night, nobody dares go out," said another villager. U.S. broadcaster Radio Free Asia said armed police had sealed roads into the area and that people were not allowed to enter or leave.

(New York Times) 20 Reported Killed as Chinese Unrest Escalates. By Howard French. December 9, 2005.

Residents of a fishing village near Hong Kong said that as many as 20 people had been killed by paramilitary police in an unusually violent clash that marked an escalation in the widespread social protests that have roiled the Chinese countryside. Villagers said that as many as 50 other residents remain unaccounted for since the shooting. It is the largest known use of force by security forces against ordinary citizens since the killings around Tiananmen Square in 1989. That death toll remains unknown, but is estimated to be in the hundreds.

The violence began after dark in the town of Dongzhou on Tuesday evening. Terrified residents said their hamlet has remained occupied by thousands of security forces, who have blocked off all access roads and are reportedly arresting residents who attempt to leave the area in the wake of the heavily armed assault.

"From about 7 p.m. the police started firing tear gas into the crowd, but this failed to scare people," said a resident who gave his name only as Li and claimed to have been at the scene, where a relative of his was killed. "Later, we heard more than 10 explosions, and thought they were just detonators, so nobody was scared. At about 8 p.m. they started using guns, shooting bullets into the ground, but not really targeting anybody.

"Finally, at about 10 p.m. they started killing people."

The use of live ammunition to put down a protest is almost unheard of in China, where the authorities have come to rely on rapid deployment of huge numbers of security forces, tear gas, water cannons and other non-lethal measures. But Chinese authorities have become increasingly nervous in recent months over the proliferation of demonstrations across the countryside, particularly in heavily industrialized eastern provinces like Guangdong, Zhejiang and Jiansu. By the government's tally there were 74,000 riots or other significant public disturbances in 2004, a big jump from previous years.

The villagers in Dongzhou said their dispute with the authorities had begun with a conflict over plans by a power company to build a coal-fired generator in their area, which they feared would cause heavy pollution. Farmers said they had not been compensated for the use of the land for the plant. Others said plans to reclaim land by filling in a local bay as part of the power plant project were unacceptable because people have made their livelihoods there as fishermen for generations. Already, villagers complained, work crews have been blasting a nearby mountainside for rubble for the landfill.

A small group of villagers was delegated to complain to the authorities about the plant in July, but they were arrested, infuriating other residents and encouraging others to join the protest movement. On Dec. 6, while villagers were mounting a sit-in demonstration, police made a number of arrests, bringing lots of people out into the streets, where they managed to detain several officers. In response, hundreds of law enforcement agents were rushed to the scene. Everybody, young and old, "went out to watch," said one man who claimed his cousin had been killed by a police officer's bullet in the forehead. "We didn't expect they were so evil. The farmers had no means to resist them."

Early reports from the village said the police opened fire only after villagers began throwing homemade bombs and other missiles, but villagers reached by telephone today denied this, saying that a few farmers had launched ordinary fireworks at the police as part of their protest. "Those were not bombs, they were fireworks, the kind that fly up into the sky," said one witness reached by telephone. "The organizers didn't have any money, so someone bought fireworks and placed them there. At the moment the trouble started many of the demonstrators were holding them, and of those who held fireworks, almost everyone was killed."

Other witnesses estimated that 10 people were killed immediately in the first volley of automatic gunfire. "I live not far from the scene, and I was running as fast as I could," said one witness, who declined to give his name. "I dragged one of the people they killed, a man in his 30's who was shot in his chest. Initially I thought he might survive, because he was still breathing, but he was panting heavily, and as soon as I pulled him aside, he died."

The witness said that he, too, had come under fire when the police saw him coming to the aid of the dying man. The Chinese government has yet to issue a statement about the incident, nor has it been reported in the state media. Reached by telephone, an official in the city of Shanwei, which has jurisdiction over the village, said, "Yes, there was an incident, but we don't know the details." The official said an official announcement would be made on Saturday.

Villagers said that in addition to the regular security forces, the authorities had enlisted thugs from local organized crime groups to help put down the demonstration. "They had knives and sticks in their hands, and they were two or three layers thick, lining the road," one man said. "They stood in front of the armed police, and when the tear gas was launched, the thugs were all ducking."

Like the Dongzhou incident itself, most of the thousands of riots and public disturbances recorded in China this year have involved environmental, property rights and land use issues. Among other problems, in trying to come to grips with the growing rural unrest, the Chinese government is wrestling with a yawning gap in incomes between farmers and urban dwellers, and rampant corruption in local government, where unaccountable officials deal away communal property rights, often for their own profit.

Finally, mobile telephone technology has made it easier for people in rural China to organize, communicating news to one another by short messages, and increasingly allowing them to stay in touch with members of non-governmental organizations in big cities who are eager to advise them or provide legal help.

Over the last three days, residents of the village say that other than people looking for their missing relatives, few people have dared go outside. Meanwhile, the police and other security forces have reportedly combed the village house by house, looking for leaders of the demonstration and making arrests.

Residents said that after the villagers' demonstration was suppressed a senior Communist Party official came to the hamlet from the nearby city of Shanwei and addressed residents with a megaphone. "Shanwei and Dongzhou are still good friends," the party official said. "We're not here against you. We are here to make the construction of the Red Sea Bay better. Later, the official reportedly told visitors, "all of the families who have people who died must send a representative to the police for a solution."

Today, a group of 100 or so bereaved villagers gathered at a bridge leading into the town, briefly blocking access to security forces hoisting a white banner whose black-ink characters read: "The dead suffered a wrong. Uphold justice."

(The Standard) Killer cops in 24-hour watch at village. December 10, 2005.

A village in southern China where paramilitary troops fired on demonstrators, killing several, has been placed under 24-hour watch as authorities try to find protest organizers, villagers said Friday. The shootings happened Tuesday during a clash between hundreds of officers in the People's Armed Police - a unit of the military - and more than 1,000 villagers protesting against the construction of a power plant in Dongzhou district of Shanwei city, Guangdong province. The special police unit opened fire after villagers set up a blockade to prevent them from entering and threw small-scale explosives used in fishing, residents and an international human rights group have said.

Villagers said Friday there were still hundreds of troops guarding the village entrance and patrolling the streets. "There are still a lot of People's Armed Police around. They brought in tanks, six of them," said a man surnamed Chen. "They are patrolling everywhere on the roads and the hill. There could be 1,000 to 2,000 of them."

Local authorities have posted notices on the streets, vowing to arrest and punish organizers, residents said. "They are trying to find the villagers' representatives ... it's very tense. We are afraid to go out except to buy food," said a woman, also surnamed Chen.

Some 50 people are missing and are feared dead or arrested, villagers said, while other residents were in hiding.

There was still no official announcement of the incident on China's state- controlled media.

Some residents said four people had died under paramilitary gunfire but Amnesty International issued a report late Wednesday saying some sources said six people had been killed. Other villagers said the death toll may be as high as 30. "There are probably 30 people who died. There were people who saw the bodies being loaded onto trucks," said the man Chen. Hospitals where the bodies have been taken, as well as the police and local and provincial governments, refused to comment.

Villagers said the clash stemmed from a long dispute over compensation they wanted from the government for taking their land to build the big coal- fired power plant. The project, sponsored by a company run by the provincial government, would also prevent villagers from using a nearby lake to earn income from fishing. Villagers said none of the police were injured as the explosives they used were weak.

With the news blackout, villagers said they feared no one would know what happened and lived in a state of fear. "Nowadays, troops kill ordinary people and blame everything on the people. Please help us ask Premier Wen Jiabao for justice for the people," Chen said.

(Xinhua) Shanwei reveals investigation report on villagers' violence in power plant. December 10, 2005.

Hundreds of villagers incited by a few instigators violently attacked a wind power plant on Dec. 6, and assaulted the police, the Information Office of the city government of Shanwei in south China's Guangdong Province said here Saturday. In an investigation report of the incident, the office called the armed assault a serious violation of law.

According to the official recount, the instigators led by Huang Xijun engineered and organized some villagers in Dongzhoukeng and Shigongzhai to illegally besiege and attack a local wind power plant at noon on Dec. 5 and Dec. 6.

The first assault on Dec. 5 caused a seven-hour suspension of the plant's power generation. In the second onslaught, over 170 armed villagers led by instigators Huang Xijun, Lin Hanru and Huang Xirang used in the attack knives, steel spears, sticks, dynamite powder, bottles filled with petroleum, and fishing detonators.

Police moving in to maintain order were forced to throw tear shells to break up the armed besiege, and arrested two insurgents. However, Huang Xijun mobilized over 300 armed villagers to form a blockade on the road to Shigongzhai Village to obstruct the return passage of the police, in attempt to threaten the police to release the arrested insurgents. For a moment, many besiegers intended to quit following the persuasion shouted by the police. However, they were forced to stay in protest under the threat reinforced by the instigators, according to the report. Instigator Lin Hanru shouted through a loudspeaker that they would throw detonators to the police and blow the wind power plant, if the police refused to retreat.

It became dark when the chaotic mob began to throw explosives at the police. Police were forced to open fire in alarm. In the chaos, three villagers died, eight were injured with three of them fatally injured. Concerned government departments are still investigating in the exact cause of the death.

The Information Office said that the instigators with Huang Xijun at the core had incited villagers to join in armed protests since June, using villagers' discontents over a land requisition of a coal-fired power plant in Dongzhoukeng Village as the excuse. They frequently formed armed protests in the construction ground of the coal-fired power plant, blocked public traffic, attacked government offices and even illegally detained people and vehicles passing through the village to threat the local government to approve more compensation fund in land requisition.

In order to magnify the effect of their protests, the instigators hatched the assault of the wind power plant in Shigongzhai Village, which had no relations with their former request for fund concerning the land requisition in Dongzhoukeng Village. The provincial government of Guangdong pays great attention to the Dec. 6 Incident. A special work group has been established to investigate in the incident, according to the Information Office.

(Ta Kung Pao) Shanwei Announced the Truth About the Honghaiwan Conflict. December 11, 2005.

[in translation]

According to Xinhua (Shanwei, Guangdong), Huang Xijun and others have been organizing Dongzhoukeng village to create incidents over the compensation for land requisitioned to bild the coal power plant. In order to create a new incident, they stirred up some villagers in nearby Shigongliao on the grounds that the wind power plant destroyed the fengshui of that village. These people surrounded and attacked the wind power plant and forced the plant to cease supplying electricity for seven hours beginning at 430pm.

After the local authorities stopped the incident and resumed the electricity supply, at 3pm on December 6, Dongzhoukeng village troublemakers Huang Xijun, Lin Hanru, Huang Xirang and others gathered more than 170 villagers armed with attack knives, steel pitchforks, wooden poles, dynamite, petroleum-filled bottles, fishing bombs (which contains dynamite and detonator and are used illegally by local fishermen to fish). They surrounded and then attacked the main control building at the wind power plant. They tossed large numbers of fishing bombs and lit petroleum-filled bottles, starting many fires inside the plants and destroying one transformer. As repeated advice was ignored, the militia policemen on duty used tear gas to disperse the crowd in order to protect public facilities. They arrested two Dongzhoukeng village troublemakers at the scene.

At around 4pm on December 6, Huang Xijun stirred up more than 300 people in Dongzhoukeng village. Armed with fishing bombs and petroleum-filled bottles, they barricaded the only road leading to Shigongliao to prevent the policemen who were carrying out their public duties there from leaving. They further demanded the public security office to release the arrested troublemakers.

In this situation, the police ordered the villagers to depart. At the time, more and more spectators were gathering, more than 500 at the peak. Certain members of the crowd wanted to leave, but the monitors set up Huang Xijun forced them to say. In order to control the situation, more police were sent by Shanwei City to maintain order.

The troublemakers led by Huang Xijun did not listen to advice, and continued to block the road and attacked the police there with rocks, fishing bombs and petroleum-filled bottles. When verbal warnings had no effect, the police fired tear gas. Due to wind direction, the effect was limited.

The scene then called increasingly out of control and Huang Xijun and leaders of the troublemakers were emboldened. Lin Hanru used a loudspeaker to 'order' the police to leave within 15 minutes or else "the entire police squad would be bombed to the ground." They also declared that they will destroy the power plant with bombs.

In the very tense situation, the police were forced to fire warning shots. As it was already dark and the conditions were very chaotic, there were misfires that led to deaths and injuries. In the entire incident, three died and eight were wounded (including 3 serious injnuries). The casualties were all from Dongzhoukeng village. When the police found the injured, they sent them to the hospital. The causes of the deaths and injuries are still being investigated. By around 9pm that evening, the crowds have dispersed and the incident was basically under control. The police dismantled the roadblocks set up by Huang Jixun and others.

(New York Times) Villagers Tell of Lethal Attack by Chinese Forces on Protesters. December 10, 2005.

Four days after a lethal assault on protesters by paramilitary forces, a village in southern China remained under heavy police lockdown on Saturday.

Residents of the village, Dongzhou, interviewed by telephone from this nearby city, said the police continued to make arrests and bar outsiders from their hamlet.

The authorities have still not commented in any detail on the incident, in which villagers said as many as 20 residents of Dongzhou were shot and killed by security forces on Tuesday night as they protested plans for a power plant, in the deadliest use of force by Chinese authorities against ordinary citizens since the Tiananmen massacre in 1989. Residents of Dongzhou said at least 42 people were missing.

Reached by telephone, the deputy propaganda chief of Shanwei, which is 15 miles to the north and has jurisdiction over the village, said the national government would issue its first statement about the incident no later than Sunday. “We will soon have a response to this, very soon — no later than tomorrow,” said the official, Liu Jingmao. “By then, this thing will be made public in the mainstream media and within the province.” Asked what he meant by “this thing,” the official cut short the conversation, saying: “I can’t say now. Anyway, it will be very soon, no later than tomorrow. That’s it.”

Later, a local television bulletin here said that three people had been killed in Dongzhou, and eight injured, describing them as “criminals” and giving no other details. This was the first known mention of the violence in China’s state-controlled media, and Beijing’s silence on the events underscored the vulnerability of a system that still practices heavy censorship in an age when sources of information beyond the government’s control are readily available.

In recent months, the Chinese government has been increasingly preoccupied with stemming thousands of demonstrations against corrupt local governments and pollution and over land-use issues. Most have taken place in rural areas and villages, far from the public eye. Dongzhou, however, is close to Hong Kong, whose television signals reach here easily, and news of the killings has spread rapidly, despite the officially imposed silence in Chinese media. In the last 24 hours, Chinese language Web sites have carried abundant reports on the killings, often picked up from foreign news outlets, and commented upon them endlessly and often angrily.

Dongzhou’s villagers, with little hesitation and much outrage, recounted more details of the events in numerous telephone calls on Saturday. Still, most asked not to be identified. Many said the authorities’ brutality against the demonstrators warranted comparison to the Japanese occupiers of the last century, and to Chinese Nationalist Army of Chiang Kai-shek.

Their accounts suggested a range of possible casualties. They identified four dead villagers, three of whom they said were taken to a local clinic, and said the fourth body was taken to a hospital in Shanwei. But they also spoke with conviction about other casualties, though often with sketchier details. Some insisted they had seen other bodies, and others spoke of large numbers of people unaccounted for.

“I was not at the scene that night, but after I heard some people were shot dead, I went to the clinic and saw three dead bodies there,” said a man who gave his name only as Chang. “The next day, I heard there were several bodies lying by the road, where tragedy took place. I went there and saw seven or eight bodies lying there in a row, surrounded by many policemen, who were denying the families’ attempts to claiming for the bodies.”

Numerous accounts said that the authorities had thrown corpses into the sea and burned bodies after the killings. Villagers said they had counted 13 bodies floating on the sea. Villagers also said that several times over the last few days, female residents had approached the police, who are still present in Dongzhou in large numbers, to beg that the bodies of relatives be released. Others said that people had quickly buried the bodies of their relatives so they could not be destroyed by the police to cover up evidence of the killings.

“I heard that they police had sent dead bodies to Haifeng to be cremated there,” said a man who gave his name as Li, and said he had been at the scene of the shootings. “Some corpses were just burned in the crossroads of the village, but not allowing people to get close to see.”In another reported episode, six unarmed men from the village fled the violence, climbing a nearby hilltop, where they were pursued by the police and shot, leaving only one survivor, whose account was repeated by villagers on Saturday. Some of the dead, the account said, were wounded from afar and then killed by the police at close range.

“That person saw with his own eyes that five people were killed,” said a man who said he had heard the account firsthand from the survivor, who was wounded in the leg. This was one of several accounts in which villagers said security forces had shot and wounded people.

The confrontation on Tuesday was the culmination of months of tension over the construction of a coal-fired power plant. Villagers said they had not been adequately compensated for the use of their land — less than $3 per family, one said — and feared pollution from the plant would destroy their livelihood as fishermen. The plans called for the village’s bay to be reclaimed with landfill. “Shanwei’s deputy party secretary said that he wanted to trample Dongzhou into a flat land,” said a village resident who gave her name as Jiang, and spoke with anger at the heavy-handed manner of the authorities before the outbreak of violence. “He said we’re just like a small hole in the ground.”

Municipal officials here have been circulating the area, blaming the villagers for initiating the violence. They said that the villagers used fireworks, blasting caps and other small explosives, and that they had rejected a generous settlement for the use of the land.

“I’m a good friend of Dongzhou people,” one party official said by megaphone as he toured the village on Saturday. “Nobody wants to see anything like what happened here on the night of Dec. 6, but the people of this village are too barbaric. We were forced to open fire.”

A 16-year-old boy who said he was in the crowd when the police began to fire said: “We didn’t use explosives, because we were too far away. Someone may have tried, but there’s no way we could have reached them. These were homemade weapons, and when they started shooting, we didn’t have a chance.’’

(Washington Post) Chinese police tighten control on rebellious town. By Edward Cody. December 10, 2005.

Armed police tightened their lockdown of a rebellious Chinese village Friday and went from house to house seeking leaders of violent clashes earlier in the week that villagers said had resulted in the deaths of more than a dozen people.

Residents reached by telephone said Dongzhou, a farming and fishing village 14 miles southeast of Shanwei city in Guangdong province near Hong Kong, was quiet Friday for the second night in a row. But checkpoints were reinforced on roads leading in and out of the village, leaving its 10,000 residents blocked in unless they traveled by sea or walked circuitous routes.

Some families were still trying to recover the bodies of those killed by pistol and automatic-weapons fire from People's Armed Police during confrontations Tuesday and Wednesday nights, the residents reported. Villagers said 14 to 20 people were shot and killed. Their estimates were impossible to confirm; government and hospital officials maintained a strict silence and prevented Chinese news media from reporting on the violence.

Over the last three days, residents of the village said by telephone, few people dared to go outside, other than to look for missing relatives. The police and other security forces, meanwhile, searched the village from house to house, residents said, looking for leaders of the demonstration and making arrests.

...

In Dongzhou, standard riot police were joined by People's Armed Police wearing camouflage fatigues and carrying automatic rifles. They opened fire, villagers said, after rioters pelted them with gasoline bombs and explosive charges that local fishermen ordinarily toss into the adjacent South China Sea to stun fish and increase their catch.

Dongzhou's residents have been engaged in a long-simmering protest against confiscations of their farmland for a wind-powered electricity plant. Compensation for the land was too low, they complained, and the project also seemed likely to ruin fishing in a tidal inlet.

A small group of villagers was chosen to complain to the authorities about the plant in July, but the members were arrested, infuriating residents and leading others to join the protests. The police made more arrests on Tuesday while villagers were mounting a sit-in, bringing many people out into the streets, where they obstructed several officers. In response, hundreds of law enforcement officers were rushed in. "Everybody, young and old, went out to watch," said one man who claimed his cousin was shot dead in the forehead by the police during the protest. "We didn't expect they were so evil. The farmers had no means to resist them."Residents said their village has been occupied since then by thousands of security officers, who have blocked off all access roads and were arresting residents who have tried to leave the area in the wake of the heavily armed assault. On Friday, about 100 bereaved villagers gathered at a bridge leading into the town, briefly blocking access to security forces. The villagers hoisted a white banner whose black-ink characters read: "The dead suffered a wrong. Uphold justice."

(SCMP) Riot village sealed off in hunt for protesters. December 10, 2005.

Hundreds of paramilitary police continued to guard a Guangdong village yesterday as evidence emerged of the deaths of villagers in the violent suppression of a riot. While police hunted for those involved in Tuesday's riot in Dongzhou village, Shanwei city , families of some victims hid the bodies of their loved ones, fearing the authorities would take them in a bid to cover up the deaths.

Villagers say dozens of people were killed or injured when police opened fire on protesters. One villager gave the South China Morning Post a photograph of one victim, Lin Yutui, a bullet hole clearly showing in his chest.

Shanwei and provincial officials, meanwhile, have either denied the shooting happened or declined to comment.

The massive police presence yesterday suggested that tensions are still running high in the village. Several hundred police - carrying shields but apparently not armed - guarded the main entries to the village and patrolled the streets. Officers carrying photos of villagers involved in the riots were on the lookout for suspects trying to leave the village and checked the identity of anyone entering. All outsiders were barred from entry. Half-a-dozen armoured personnel carriers and vehicles with water cannon were deployed across the village and near the site of Tuesday's clash.

Villagers had been protesting against the construction of a power plant in the village, complaining that their land was taken away without adequate compensation. In a showdown on Tuesday, hundreds of armed police battled with the protesting villagers, who fought back with crudely made Molotov cocktails. Villagers said police then opened fire on the crowd.

Liu Jingmao , a vice-director of the Shanwei Propaganda Department, said yesterday the city government would give a public account of what happened but refused to confirm that villagers had been shot dead by police. But villagers are afraid of a cover-up. "We fear they are attempting to destroy all the evidence because they insist so far that no one has been killed," one said.

Another villager whose relative, 31-year-old Wei Jin, was killed in the shooting, said local officials had offered the family hush money if they surrended Wei's body. "They offered us a sum but said we would have to give up the body," the villager said. "We are not going to agree." Other villagers remain unaccounted for and families fear they are victims of Tuesday's confrontation. Dozens of women yesterday knelt in front of policemen at the clash site, begging for the bodies of their husbands or sons.

The clash in Dongzhou was not reported in any mainland media and local hospitals refused to say if they had received any injured.

Rumours circulated in the village yesterday that a vice-director of the local public security bureau had been suspended and that senior provincial leaders had arrived to investigate.

(SCMP) Villagers fear reprisals against rioters. December 11, 2005.

Dongzhou villagers in Guangdong yesterday said they fear authorities will soon take action against people involved in a riot that was violently suppressed last week. The clash in the village of Shanwei city resulted in the death of three civilians, according to authorities, who added it was now classified as a case of "serious violence against the people's police by several hundred villagers that was instigated by a small number of people".

One villager whose relative was wounded in the crackdown said yesterday he had been told the police would lock up those they could prove had taken part in the protests.

"We just spent 20,000 yuan on surgery to save him [the relative] after he was shot in the chest," the villager said. "But he is now under effective police custody at Shanwei People's Hospital after he was interviewed by television reporters from Hong Kong last Wednesday."

The villager said that at least four officers were guarding his relative and family who came to visit were not allowed to return home. "Other family members cannot visit him at the hospital now," he said.

Local sources said a senior Shanwei city official visited the widow of Wei Jin late on Friday and offered the family 2,000 yuan in condolence money. Wei, 31, was killed in the clash. He is survived by a wife and two sons.

A woman whose husband suffered minor injuries believed all the injured villagers were now under police control. "Actually, no injured villagers are not allowed to meet outsiders, especially reporters from Hong Kong," she said.

A 57-year-old man, who did not protest but was hit in the head by a tear gas canister, said he saw the police shooting. "I went [to the riot site] to have a look because I was curious," said the man who declined to give his full name, but was willing to be photographed. "But there [police fired] tear gas and I heard gunshots after flashes of bright light. "I went to the Dongzhou health station and heard the doctor saying two men were confirmed dead."

In earlier reports, villagers claimed that they took to the streets because they opposed the construction of a power plant and inadequate compensation for their land.Several village women and victims' relatives yesterday continued to sit outside the Dongzhou police station, which is only metres from the scene of the riot. The site - at an intersection that is a key entry point into the village - was still being guarded by about 100 policemen, but the barricades had been moved back about 30 metres since Friday. On Friday, dozens of women knelt in front of policemen, begging them to return the bodies of their husbands or sons. Yesterday, local officials put up banners reminding villagers that they should not believe in rumours and report suspects to the authorities. Political slogans such as "People's Armed Police are for the people" were also posted in the village.

(Los Angeles Times) China Defends Police Shooting of Villagers. By Mark Magnier. December 11, 2005.

The Chinese government broke its silence Saturday on a deadly clash in southern China last week, insisting that police used deadly force only after a "few instigators" threatened them with explosives.

In the first official response since the incident late Tuesday, the state-run New China News Agency said three villagers were killed and eight wounded in the clash in the village of Dongzhou, in Guangdong province near Hong Kong.

In telephone interviews, locals said police killed as many as 20 farmers who were demanding compensation for land seized to build a wind power plant.

The official news agency, quoting authorities from the neighboring city of Shanwei, said police used tear gas to break up a mob of about 170 villagers armed with sticks, knives, steel spears and explosives in the hours before the fatal clash. The villagers' actions were "a serious violation of the law," the authorities said, promising an investigation.

Riot squads armed with machine guns and shields have ringed Dongzhou, blocking outsiders from entering, and villagers charged that authorities were mounting a cover-up. But in telephone interviews today, residents gave their version of events.

"It happened at night, so it's very hard to tell exactly how many died," said a woman who gave her last name as Liu. Like most villagers, she declined to give her full name out of fear of retribution. "But at least 10 were shot and many are still missing."

Both sides say the catalyst was a police decision to arrest local protest leaders.

A farmer named Zhang, 50, said officials detained one of the leaders about noon Tuesday. That evening, he said, police headed toward a construction site, and villagers, believing they were going to detain more people, blocked their way. Police fired tear gas and shot their guns into the air, he said.

As tension built, villagers told police they had homemade explosives and would detonate them if the officers didn't turn around. "Protesters did detonate explosives," Zhang said. "But it was only a threat, and no official or police were hurt." At that point, officers opened fire on the protesters.

Villagers, several of whom said they believed their phones were tapped, said at least eight protesters were arrested Saturday. Most were impoverished farmers with families to support.

"The military is right outside our door," said one woman, 24, who declined to give her name. "People are crying all the time. We knelt down in front of the military yesterday and begged them not to come into our village and arrest people. But they wouldn't listen."

Villagers said there had been cases of police offering money to families of the dead, possibly in an effort to keep them quiet. One resident said villagers had hidden two bodies to prevent police from taking them and denying that they were killed. As with much of the account, this could not be independently confirmed.

(Apple Daily via ChineseNewsNet) December 11, 2005.

[in translation]