Michelangelo Antonioni and Chung Kuo

The Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni has just passed away. The following post originally appeared on December 4, 2004 in the original version of EastSouthWestNorth, and it is being brought back as a review of the director's work.

The Globe & Mail article below reports that Michelangelo Antonioni's Chung Kuo was finally shown in China. This is enough to make me nostalgic for the days when I actually studied the official articles of condemnation. Here is the principal article:

A Vicious Motive, Despicable Tricks -- A Criticism of Antonioni's Anti-China Film "China" (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1974), an eighteen-page pamphlet (unsigned) which reproduces an article that appeared in Renming Ribao on January 30, 1970.

Unfortunately, I did not keep a copy of this masterpiece, which was a delight for me to read (but for all the 'wrong' reasons) at the time. But unless the reader is of a certain age, this irony of the above comment will probably elude him/her. You will have to imagine how 800 million Chinese people were mobilized into a mass criticism campaign for a movie that none of them had seen, and that all of what they subsequently said was based upon fanciful imagination and internal projection while trying to guess what the higher-up authorities wanted them to say (as well as not say).

Umberto Eco's explanation for the Chinese reception of the Antonioni move was based upon connotative conventions.

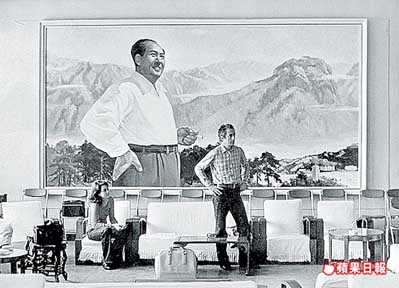

An example taken from an Antonioni movie can clarify the difference between denotative and connotative conventions. You probably know that Antonioni's China-Chung Kuo, a movie the artist directed in a genuinely sympathetic mood, has been interpreted by Chinese critics as an unbearably denigratory pamphlet directed against the Chinese people. Now if one analyzes frame by frame and sequence by sequence all the cases in which Chinese critics and authorities charge Antonioni with unfriendly attitudes, one realizes that they are all cases in which Chinese addressees have superimposed different connotative subcodes on the ones foreseen by the author. Among the sequences which have most offended Chinese audiences is one in which the camera shows the Nanking Bridge. The Chinese say that Antonioni has tried to give the impression that the bridge is unstable and on the verge of collapsing. If you look at the movie you can see that the director has shown the bridge, by passing underneath it moving the camera in a circular manner, from a sort of "expressionistic" point of view. This has the effect of privileging oblique angles, transverse perspectives, and asymmetric frames, as any western movie-maker does when he wants to suggest power and architectural impact. But present Chinese iconographic subcodes are obviously different, as anybody can see when looking at a Chinese movie like The Girl of the Red Guards Detachment, or a propaganda mural painting: Chinese iconography is based on symmetrical and frontal frames with a sort of neoclassical mood and they express power, stability, monumentality only by frontal and symmetric shots. The denotation was the same (it was for the Nanking Bridge) but the connotations were based on different subcodes.

Now I don't find that convincing at all. The much better explanation is given in Susan Sontag comments on Chung Kuo from the book On Photography. As usual with Sontag, this is hardly about this particular movie but extends to the rest of life:

Nothing could be more instructive about the meaning of photography for us -- as, among other things, a method of hyping up the real -- than the attacks on Antonioni's film in the Chinese press in early 1974. They make a negative catalogue of all the devices of modern photography, still and film.

While for us photography is intimately connected with discontinuous ways of seeing (the point is precisely to see the whole by means of a part -- an arresting detail is a striking way of cropping), in China it is connected only with continuity. Not only are there proper subjects for the camera, those which are positive, inspirational (exemplary activities, smiling people, bright weather), and orderly, but there are proper ways of photographing, which derive from notions about the moral order of space that preclude the very idea of photographic seeing.

Thus Antonioni was reproached for photographing things that were old, or old-fashioned -- "he sought out and took dilapidated walls and blackboard newspapers discarded long ago"; paying "no attention to big and small tractors working in the fields, [he] chose only a donkey pulling a stone roller" -- and for showing undecorous moments -- "he disgustingly filmed people blowing their noses and going to the latrine" -- and undisciplined movement -- "instead of taking shots of pupils in the classroom in our factory-run primary school, he filmed the children running out of the classroom after a class."

And he was accused of denigrating the right subjects by his way of photographing them: by using "dim and dreary colors" and hiding people in "dark shadows"; by treating the same subject with a variety of shots -- "there are sometimes long-shots, sometimes close-ups, sometimes from the front, and sometimes from behind" -- that is, for not showing things from the point of view of a single, ideally placed observer; by using high and low angles -- "The camera was intentionally turned on this magnificent modern bridge from very bad angles in order to make it appear crooked and tottering"; and by not taking enough full shots -- "He racked his brain to get such close-ups in an attempt to distort the people's image and uglify their spiritual outlook."

Besides the mass-produced photographic iconography of revered leaders, revolutionary kitsch, and cultural treasures, one often sees photographs of a private sort in China. Many people possess pictures of their loved ones, tacked to the wall or stuck under the glass on top of the dresser or office desk. A large number of these are the sort of snapshots taken here at family gatherings and on trips; but none is a candid photograph, not even the kind that the most unsophisticated camera user in this society finds normal -- a baby crawling on the floor, someone in mid-gesture. Sports photographs show the team as a group, or only the most stylized balletic movements of play: generally, what people do with the camera is assemble for it, then line up in a row or two. There is no interest in catching a subject in movement.

This is, one supposes, partly because of certain old conventions of decorum in conduct and imagery. And it is a characteristic visual taste of those at the first stage of camera culture, when the image is defined as something that can be stolen from its owner; thus Antonioni was reproached for "forcibly taking shots against people's wishes," like "a thief."

Possession of a camera does not license intrusion, as it does in this society whether people like it or not. (The good manners of a camera culture dictate that one is supposed to pretend not to notice when one is being photographed by a stranger in a public place as long as the photographer stays at a discreet distance -- that is, one is supposed neither to forbid the picture-taking nor to start posing.) Unlike here, where we pose where we can and yield when we must, in China taking pictures is always a ritual; it always involves posing and, necessarily, consent. Someone who "deliberately stalked people who were unaware of his intention to film them" was depriving people and things of their right to pose, in order to look their best.Antonioni devoted nearly all of the sequence in Chung Kuo about Peking's Tien An Men Square, the country's foremost goal of political pilgrimage, to the pilgrims waiting to be photographed. The interest to Antonioni of showing Chinese performing that elementary rite, having a trip documented by the camera, is evident: the photograph and being photographed are favorite contemporary subjects for the camera. To his critics, the desire of visitors to Tien An Men Square for a photographic souvenir:

is a reflection of their deep revolutionary feelings. But with bad intentions, Antonioni, instead of showing this reality, took shots only of people's clothing, movement, and expressions: here, someone's ruffled hair; there, people peering, their eyes dazzled by the sun; one moment, their sleeves; another, their trousers. ...

The Chinese resist the photographic dismemberment of reality. Close-ups are not used. Even the postcards of antiquities and works of art sold in museums do not show part of something; the object is always photographed straight on, centered, evenly lit, and in its entirety.

We find the Chinese naïve for not perceiving the beauty of the cracked peeling door, the picturesqueness of disorder, the force of the odd angle and the significant detail, the poetry of the turned back. We have a modern notion of embellishment -- beauty is not inherent in anything; it is to be found, by another way of seeing -- as well as a wider notion of meaning, which photography's many uses illustrate and powerfully reinforce. The more numerous the variations of something, the richer its possibilities of meaning: thus, more is said with photographs in the West than in China today.

Apart from whatever is true about Chung Kuo as an item of ideological merchandise (and the Chinese are not wrong in finding the film condescending), Antonioni's images simply mean more than any images the Chinese release of themselves. The Chinese don't want photographs to mean very much or to be very interesting. They do not want to see the world from an unusual angle, to discover new subjects. Photographs are supposed to display what has already been described. Photography for us is a double-edged instrument for producing clichés (the French word that means both trite expression and photographic negative) and for serving up "fresh" views. For the Chinese authorities, there are only clichés -- which they consider not to be clichés but "correct" views.

In China today, only two realities are acknowledged. We see reality as hopelessly and interestingly plural. In China, what is defined as an issue for debate is one about which there are "two lines," a right one and a wrong one. Our society proposes a spectrum of discontinuous choices and perceptions. Theirs is a constructed around a single, ideal observer; and photographs contribute their bit to the Great Monologue. For us, there are dispersed, interchangeable "points of view"; photography is a polylogue.

The current Chinese ideology defines reality as a historical process structured by recurrent dualisms with clearly outlined, morally colored meanings; the past, for the most part, is simply judged as bad. For us, there are historical processes with awesomely complex and sometimes contradictory meanings; and arts which draw much of their value from our consciousness of time as history, like photography. (This is why the passing of time adds to the aesthetic value of photographs, and the scars of time make objects more rather than less enticing to photographers.)

With the idea of history, we certify our interest in knowing the greatest number of things. The only use the Chinese are allowed to make of their history is didactic: their interest in history is narrow, moralistic, deforming uncurious. Hence, photography in our sense has no place in their society.

The limits placed on photography in China only reflect the character of their society, a society unified by an ideology of stark, unremitting conflict. Our unlimited used of photographic images not only reflects but gives shapes to this society, one unified by the denial of conflict. Our very notion of the world -- the capitalist twentieth century's "one world" -- is like a photographic overview.

The world is "one" not because it is united but because a tour of its diverse contents does not reveal conflict but only an even more astounding diversity. This spurious unity of the world is affected by translating its contents into images. Images are always compatible, or can be made compatible, even when the realities they depict are not.

Photography does not simply reproduce the real, it recycles it -- a key procedure of a modern society. In the form of photographic images, things and events are put into new users, assigned new meanings, which go beyond the distinctions between the beautiful and the ugly, the true and the false, the useful and the useless, good taste and bad. Photography is one of the chief means for producing that quality ascribed to things and situations which erases these distinctions: "the interesting." What makes someting interesting is that it can be seen to be like, or analogous to, something else. There is an art and there are fashions of seeing things in order to make them interesting; and to supply this art, these fashions, there is a steady recycling of the artifacts and tastes of the past. Clichés, recycled, become meta-clichés. The photographic recycling makes clichés out of unique objects, distinctive and vivid artifacts out of clichés. Images of real things are interlayered with images of images. The Chinese circumscribe the uses of photography so that thee are no layers or strata of images, and all images reinforce and reiterate each other.* We make of photography a means by which, precisely, anything can be said, any purpose served. What in reality is discrete, images join. In the form of a photography, the explosion of an A-bomb can be used to advertise a safe.*The Chinese concern for the reiterative function of images (and of words) inspires the distributing of additional images, photographs that depict scenes in which, clearly, no photograph could have been present; and the continuing use of such photographs suggests how slender is the population's understanding of what photographic images and picture-taking imply. In his book Chinese Shadows, Simon Leys give an example from the "Movement to Emulate Lei Feng," a mass campaign of the mid-1960s to inculcate the ideals of Maoist citizenship built around the apotheosis of an Unknown Citizen, a conscript named Lei Feng who died at twenty in a banal accident. Lei Feng Exhibitions organized in the large citizens included "photographic documents, such as 'Fei Feng helping an old woman to cross the street,' 'Lei Feng secretly [sic] doing his comrade's washing,' 'Lei Feng giving his lunch to a comrade who forgot his lunch box,' and so forth," with, apparently, nobody questioning "the providential presence of a photographer during the various incidents in the life of that humble, hitherto unknown soldier." In China, what makes an image true is that it is good for people to see it.

(Globe and Mail) China lifts ban on film icon. By Geoffrey York. November 2, 2004.

The great Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni was at the height of his fame and his creative powers when he came to China in 1972 to document the revolution. He had the blessing of Communist authorities and was an intellectual left-winger who sympathized with China's new society.

When he completed his cinematic portrait of workers and farmers in China's cities and villages a few months later, he could never have guessed that it would be 32 years before the documentary would be shown freely to a Chinese audience.

To Mr. Antonioni's shock and confusion, his film was vilified by the Communists, who denounced him as anti-Chinese and "a worm who speaks for the Russians." His films were banned by the hard-liners who had seized control of China at the peak of the Cultural Revolution, and he became the target of relentless, vitriolic attacks in the state news media. Under pressure from Beijing, several foreign screenings of the film were cancelled, and Italy's Communists picketed his appearance at a Venice film festival.

Three decades later, still alive but in poor health, the filmmaker has at last achieved victory over his persecutors. When his four-hour documentary was screened to 800 people at the Beijing Film Academy as part of an Antonioni retrospective last weekend, it marked a moment of vindication for the 92-year-old director — and a significant shift in China's cultural policies.

It was the first public screening in China of the film, entitled Chung Kuo (the Chinese name for the country).

Indeed, it was the first time any film by Mr. Antonioni had been shown in China; they were all banned after the documentary controversy.

The director, celebrated in the West for enigmatic art-house favourites such as L'Avventura and Blow-Up, has been unable to speak more than brief syllables since suffering a near-fatal stroke in 1985. He was too ill to fulfill his long-held dream of seeing his film shown in China, but his wife, Enrica, sent a letter to the Beijing audience on his behalf.

"The idea that Chung Kuo can now be publicly seen in Beijing gives him enormous satisfaction and totally vindicates his efforts," she wrote. "Michelangelo regards this as a sign of great opening-up and change on the part of the Chinese side."

The documentary was proposed by Italian officials in 1971, shortly after Italy (and Canada) established diplomatic relations with Communist China for the first time. The idea was approved by Beijing, and Mr. Antonioni spent five weeks filming in 1972, shooting 80 hours of footage of a country that was still in the throes of the Cultural Revolution and that foreigners rarely visited.

In its first screening in Rome in early 1973, Chinese diplomats praised the film. But soon it was caught up in a Beijing power struggle. Hard-line zealots from the "Gang of Four," led by Mao Zedong's wife, Jiang Qing, used the film as a hammer against their rival, Premier Zhou Enlai, who was seen as an architect of the opening to the outside world.

The hard-liners complained that a foreign "imperialist" had been allowed to "defame the revolution and insult our people." In an editorial in the People's Daily in 1974, Mr. Antonioni was denounced for showing "unfruitful lands, lonely old people, tired animals and ugly houses."

The director was deeply hurt by the attacks and by the Italian government's failure to defend him. His bitterness continued for many years. After the economic changes that followed Mao's death, Chinese officials approached the filmmaker in the early 1980s to see whether he might be willing to visit China again. He demanded an apology for the attacks, but the Chinese refused and the visit never was made. In 2002, both sides talked of screening the film in China, but the idea was scuttled at the last minute when Beijing changed its mind.

Despite the vast changes in China in recent years, it took courage for Beijing to allow the film to be screened today, Italian officials said. The Cultural Revolution remains a sensitive and ambiguous subject for Chinese authorities, who have never apologized for the millions of lives it shattered. In Mr. Antonioni's case, the decision to screen his films is as close to an apology he is likely to get.

"It's a small, hesitant change, but a change," an Italian diplomat said. "It's a way for the new leadership to show the changes without much risk to themselves."

Chung Kuo bears all the marks of Mr. Antonioni's distinctively oblique style, the same enigmatic approach that caused such controversy in the cinema world when L'Avventura was released in 1960. The film contains not a single interview and not a single sentence of political analysis. The filmmaker deliberately rejected the conventions of script or story.

"I went to China not in order to know it but to have a look and to record what was passing in front of my eyes," he said later.

The film succeeds as an artistic work and as a portrait of ordinary life in an isolated country. With his customary detached tone and extremely long takes, the camera gazes at the Chinese people, their faces and movements. Long scenes pass without a word beyond the hubbub of background conversation and the sound of bicycle bells and street noise.

"Even today, the film is still fresh and natural and modern," said Mr. Antonioni's long-time collaborator, Italian director Carlo di Carlo, who helped edit the documentary in 1972. "What's very important is the slowness and reflectiveness of it, which is very Chinese, in a way. Antonioni's film language, in its understanding of time and space, is very close to the Chinese aesthetic."

The film's narrator makes it clear that the authorities had tried to control Mr. Antonioni's camera, forcing him to shoot some street scenes secretly. But the film remains sympathetic to the Communist regime, praising it for reducing malnutrition and even expressing envy for the leisurely pace of life in Chinese cities. "There seems to be neither anxiety nor hurry," the narrator says.

For the audience in Beijing, the film was a journey to a land long ago and far away, as alien as any distant galaxy. Most of the audience members were young people who knew little of the Cultural Revolution beyond the stories they might have heard from their parents. They gazed in fascination at the women in pigtails and drab clothing, the men in Mao suits and badges, the mud streets lacking any billboards, souvenir stands or glitzy trappings of today's capitalist economy.

Many of the Chinese audience members could not help laughing at the Maoist songs and revolutionary posters that the film captured. They giggled when an elderly woman explained that she had few grandchildren because "to build a socialist society, small families are better." They chuckled at the scenes of kindergarten children marching like Chinese soldiers, singing songs of praise to the People's Liberation Army.

"The people in those times were affected too much by propaganda," said Zheng Tianxin, a 19-year-old university student who attended the film. "They had even lost the ability to revolt."

Xu Qi, a 26-year-old bank clerk, said she was glad the film was no longer banned. "Certainly it was not a propaganda film," she said. "If anyone held such a view, it's a big insult to a real artist like Antonioni. A true artist will never obey the requirements of others."

Related Link: 逝者 安东尼奥尼在中国 纵横周刊